In January of this year, I reached 40 years of living with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Over that time, I’ve learned a lot about managing T1D and have been able to get results that satisfy me for some years now. What that means in numbers for the folks who want numbers (skip to the next paragraph if you don’t care to read numbers or don’t know what these things mean): my A1c in % is typically in the mid-5’s. My last two A1c’s were 5.5% or 37 mmol/mol. My 90-day time in range using the international standard 3.9-10 mmol/L (70-180 mg/dl) is typically around 90-92% in range, with the remainder evenly split between low and high. My 90-day standard deviation floats between 1.6-1.9 mmol/L (29-34 mg/dl) and my coefficient of variation is always below 36% and often below 30%. I strive for 0% low but spend a fair amount of time steadily coasting along at 3.7-3.8 mmol/L or 67-68 mg/dl, and I know that nondiabetic people run flat at those numbers, too. My real lows are usually mistakes on my part about when food would be ready or how my body would digest it. My time spent high is usually due to site problems, mistakes on my part about how a food will hit, and me being too slow to get all my winter gear on and get out the door after I’ve deliberately underbolused prior to exercise.

My childhood management was not as good. I had a lot of severe hypos as a child and became way too familiar with the feeling of coming to consciousness and vomiting post-glucagon. Then, from too early an age, my T1D management was left up to me, with insufficient parental oversight. After our mom left our dad and our dad moved overseas, my younger sister and I would often get our own groceries and meals. I have memories of eating cereal for all my meals and going to medical appointments on my own, if I went at all. For a while during my teens, I was the only person in the house with a job. When my mom, sister and I moved thousands of kilometres away to a new city in a new province during my teen years, my mom did not transfer my care to a new diabetes care team. She did, however, ask me why I “chose” to have diabetes and encourage me to repeat mantras about, “the sweetness of life.” This, to say the least, was not a great substitute for seeing an endo or diabetes educator. I went years without ever seeing getting any diabetes-specific care. I had a family doctor who would write prescriptions for the same old insulin, but never reviewed my records, updated my insulin, nor ensured I saw anyone with more diabetes knowledge. As I got older, I moved on and focused on doing the best I could as an adult, but that’s the reality of my history. The further I get from that history, the more I can see how it shaped my feelings and goals about T1D and the rest of my life.

I don’t always do much for my anniversary of diagnosis, or diaversary. Seven years ago, I made a list of 33 things I’d learned in 33 years with T1D. This year, I decided to write a longer post that required more time to reflect, distill, and write about management-focused lessons I’ve learned over the years. I wrote this over the course of many months. I initially thought I would post it on my diaversary, but I wasn’t anywhere near done! I kept poking away at it as I could find bits of time to reflect and write, so here it is, finally, after about six months of writing a paragraph or two whenever I had time. (Hopefully all the links still work.)

Below are some of my reflections and lessons learned about managing T1D for 4 decades. I present them here alphabetically by category, in the hopes that they might prove useful to at least one other person with T1D out there. I have gotten so much useful how-to information from fellow T1Ds, and I always aim to share my own useful information when I can. Please feel free to take and share anything that works for you, and leave the rest.

Note to those without T1D (can we call you pancreatypicals?): this is not a 101-level post. It’s written for others managing T1D (their own or someone else’s) who already understand terms. If you care about people with T1D and can manage it, please consider donating to organizations like T1International, Life For A Child, and JDRF, and please support legislative efforts where you live to make diabetes management tools (medication, technology, education, care, support) available to everyone who needs them. If you are new to T1D and don’t know some of these terms, I recommend the Juicebox podcast Defining Diabetes series.

Topics:

- 10 Most Valuable Lessons

- Attitudes & Beliefs

- Backcountry Camping

- Biggest Bang for the Buck

- Burnout

- Comfort In, Dump Out

- Complications

- Consistency

- Control

- Daily Kit

- Data & Reports

- Energy Up Front

- Fibre

- Finances & Insurance

- Highs & Spikes

- Hypos

- Insulin

- Logging Food

- Looping

- Matching Insulin & Food

- Mental Health & Stress Management

- Oops

- Outdoors

- Parenting

- Perimenopause

- Physical Activity (Exercise)

- Physical Activity (Exercise) with Insulin on Board (IOB)

- Podcasts

- Prebolusing

- Pregnancy & Breastfeeding

- Protein & Fat

- Repeated Foods

- Rollercoaster, Get Off The

- Routines & Rituals

- Science & Research

- Settings, Having A Record Of

- Sleep

- Support

- Technology & Tools

- Travel

- Water

- Weighing Food

- Weight Management

- Zealots

- Thank you

10 Most Valuable Lessons

Reflecting on which of the lessons below have been the most useful to me, I offer my assessment of which 10 lessons were probably the most valuable to me over the past 40 years:

- Believing that I am worthy of care helps me take better care of myself and my T1D.

- More in: Attitudes & Beliefs

- I can exercise without going low even if I have insulin on board (IOB) by accounting for the fact that IOB gets multiplied by an average of 3X for me during exercise.

- “accounting for” = deliberately underdosing insulin to reduce the amount of IOB leading into activity and/or covering the multiplied IOB with fast-acting carbs

- More in: Physical Activity (Exercise) with Insulin on Board (IOB)

- The bolus strategy that works best for me when it comes to larger meals (>500 calories or so) is to bolus for carb grams as usual about 12 minutes before eating, then bolus for protein grams x 0.4 an hour afterwards, and fat grams x 0.9 three hours afterwards.

- More in: Protein & Fat

- Drinking 2-3L of water per day makes insulin, food, sensors, etc. work more smoothly for me.

- More in: Water

- T1D adds stress to my life and can be tough on my mental health. The best stress management and mental health support techniques for me are: exercise (I run a lot), sleep, getting outside, and connecting with others with T1D, either actively by communicating with others or passively by listening to podcasts or reading.

- More in: Mental Health & Stress Management

- T1D is going to consume more of my energy than I’d like. (What I’d like is for it to consume none.) I don’t have a choice about whether the energy consumption will happen, but I have some control over when it happens. When I put in energy up front by prebolusing, weighing food so my boluses are bang on, bolusing with post-meal activity in mind, and other such things, I can take it a bit easier afterwards, because T1D is less likely to suck energy out of me due to bouncing blood sugars.

- More in: Energy Up Front, Weighing Food, and Prebolusing

- Eating lots of fibre means I get to eat lots of good food, my meals absorb more smoothly with fewer spikes, and my insulin-to-carb ratio is substantially lower than when I don’t eat as much fibre.

- More in: Fibre

- Technology helps me tremendously. If I had to pick just one technology, it would be continuous glucose monitoring, but my closed loop (automated insulin delivery) system has been life-changing, and is one of the major advances made possible by combining pumps, CGM, and algorithms. My eternal gratitude to everyone involved in pushing this tech forward, especially the volunteers in the #WeAreNotWaiting community.

- More in: Technology & Tools and Looping

- When my settings are right, everything is easier. The easiest way for me to get my settings right is usually by starting from general guidelines (sometimes provided by my healthcare team, sometimes from literature), then taking notes on how things are working, adjusting as needed, taking more notes, rinsing & repeating.

- T1D is expensive, including in Canada. Staying organized about insurance and paperwork helps me minimize out-of-pocket costs.

- More in: Finances & Insurance

Attitudes & Beliefs

Shorter version: Taking care of my T1D requires taking care of myself. To do this well, I had to develop the belief that I am worthy of care. (next section)

Longer version: The most useful attitude for me for living with T1D challenges has been: I’ve handled other T1D challenges before. I can handle this, too. The most useful belief for me has been: I am worthy of care. I became much more able to manage T1D well when I started believing that as an adult.

In recent years, I’ve also done things to care for myself because I want to be here for my kids long-term. But for me, at least, the core belief that I had to acquire to truly take care of myself was that, regardless of who else is or isn’t counting on me, I am worthy of care for my own sake. (You are, too.)

Backcountry Camping

Shorter version: For trips where water is plentiful, gatorade powder is light and efficient for hypo treatment/avoidance. Charging devices overnight can drain portable batteries unnecessarily, so it’s worth charging during the day. Morning oatmeal works ok with a longer (about 3x), smaller (about 50%) prebolus. Putting a silicon absorber in a dry bag with devices/supplies is cheap and can help protect from water damage in wet conditions. A 50% override (i.e., using only half of my usual insulin amounts, basal and bolus) seems to work well for both hiking and paddling days. I also increase my targets during backcountry trips for extra safety. You can’t turn off Share in the Dexcom app without internet so if the little red bubble is going to bother you like it bothers me, turn off Share before you leave cell range. I have found it comforting (when not needed) and useful (when needed) have plentiful backup supplies and screenshots of tech troubleshooting just in case. (next section)

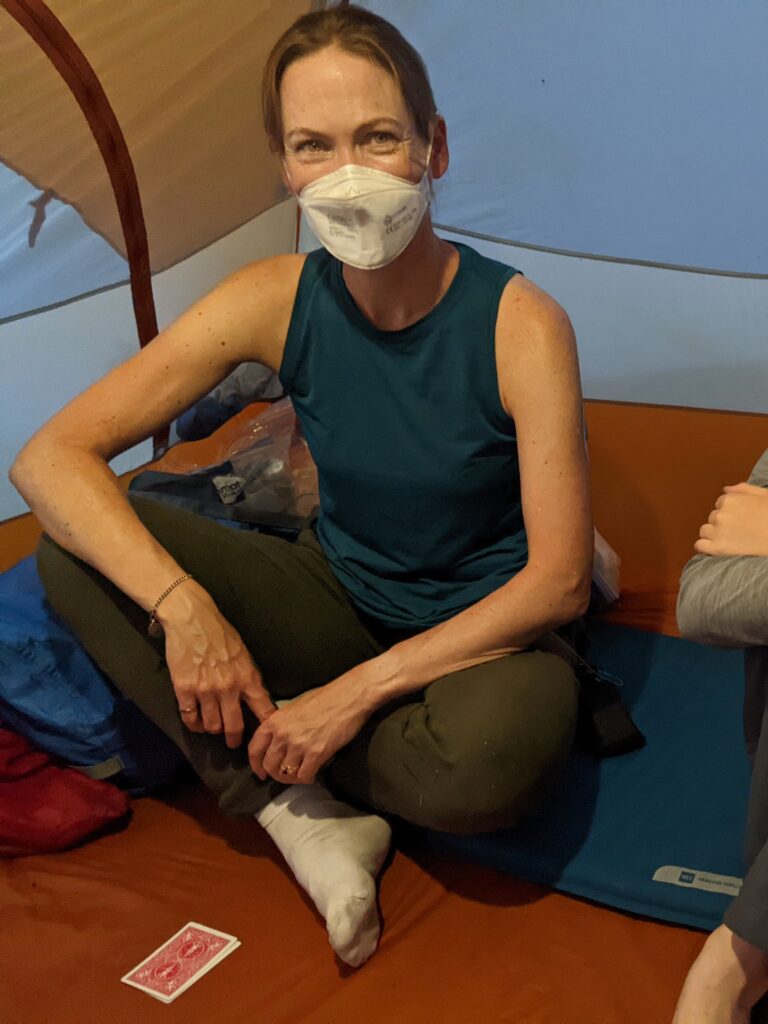

Longer version: Backcountry camping is when you hike or paddle into the woods. You may end up days away from medical help. Frontcountry camping is when you can drive to your campsite or very close to it. Like most things, backcountry camping is possible with T1D, it just takes a bit of extra planning to do it safely.

I really enjoy being away from everything in the woods. It is the only time I am able to truly ignore thoughts of work I could be doing.

Over the years, I’ve typically managed to do one or two trips each year. I did a mix of kayaking, canoeing and hiking with friends or my dad as a young adult, a lot of canoeing when my kids were small, and now that my kids are older, we’ve done some paddling and some more ambitious hikes, and I’ve also gone out for a shorter time with friends.

My most helpful backcountry-related lessons have been:

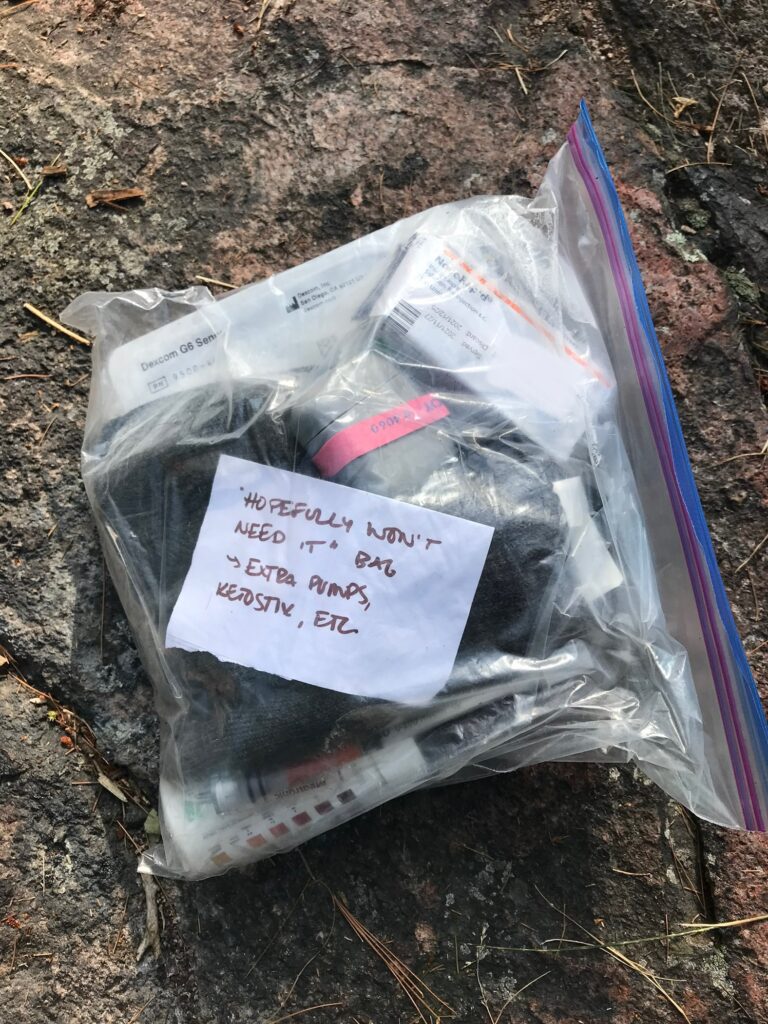

- Pack lots of backups. The downside is that I then have to carry them, but when I am days away from medical help, the peace of mind has been worth it to me and my family/group. With my current system, I bring one or more backups for each piece of equipment, plus backup long- and short-acting insulin so I could revert to multiple daily injections if needed. I show everyone on the trip how to administer glucagon if needed, and we agree on an easy-access place to always keep the glucagon. I bring at least two glucagon sources, plus gel that can be squeezed and rubbed into my cheek.

- Use Gatorade powder as my primary approach for treating/preventing lows. It’s lighter than most other low treatments. It would be bad news if the powder got wet, so I carry it in a small ziploc inside a larger ziploc, and the whole thing goes inside a dry bag of drinks and snacks. I mix it with treated or filtered water, then sip or drink as needed. On a 10-day trip this past summer, I used nearly a full can of powder by the end of the trip. (That level of use was as planned, and I still had other backup low treatments in the form of glucose gels, a few tubes of glucose tabs, some wrapped candies that fit nicely in a pocket while hiking with a heavy pack, etc.)

- Charge diabetes devices during the day, not at night. I learned this from a Backpacking Light podcast. Some devices (especially Apple devices, like my phone) will draw energy from a battery anytime they are plugged in, even if they are technically 100% charged. Plugging them in all night wastes power, which may increase the number of (heavy) rechargers needed.

- I can make oatmeal work without having to stress about leaving camp and getting moving right away (my former approach) by giving half my usual prebolus, doubling or tripling my prebolus time, eating the oatmeal, turning on a 50% override, packing up, then, if needed, drinking a bit of Gatorade before walking to balance out insulin on board.

- Diabetes devices go in dry bags with a silicon absorber. I use an older tubed pump, and I use this Aquapac case when canoeing. When hiking, I just bundle the pump and linkage device together into a small dry bag and have the tubing come out diagonally so I can fold over to maintain water resistance without compromising tubing.

- Some uncovered carbs are ok when working hard, but overdoing the uncovered snacks is a mistake. (Note to self: even though I am burning a lot of energy all day, gummi bears hit hard and require some insulin after 3 or 4 bears!)

- Overall, a 50% override is about right for me for most backcountry days. This means that I require about half as much insulin as usual when hiking/paddling all day; i.e., half the usual basal, half the usual bolus for food, and so on. Once at camp for the night, I typically turn it to more like 85%. I also increase my target from 5.0 mmol/L (90 mg/dl) to 6.3 mmol/L (113 mg/dl) and raise my suspend threshold from 4.0 mmol/L (72 mg/dl) to 5.0 mmol/L (90 mg/dl) for the whole trip.

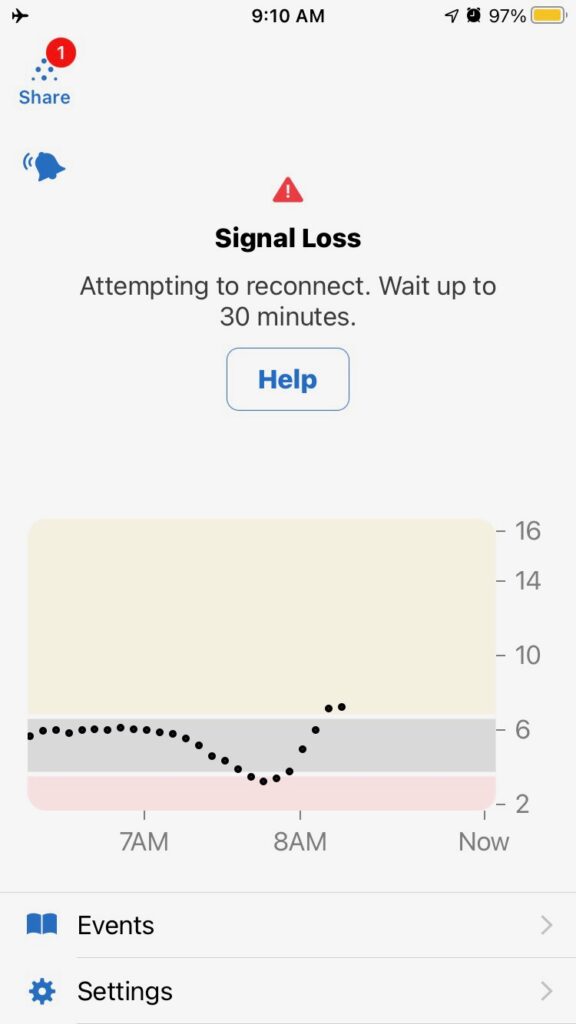

- Delete any previous transmitters and unused devices from my phone’s Bluetooth list to reduce the chance of signal loss and oh my goodness, turn off share BEFORE leaving cell range. You can’t turn it off without internet service, so when I forget to do it before leaving cell range, the Dexcom app spends the entire trip reminding me that my readings are not being shared. (Thanks, Dexcom, especially since the only person who follows my numbers is on the trip with me!)

- The dog carries his own food. (Uh, this isn’t really diabetes-related, except for the fact that I have to carry extra diabetes supplies, so it’s more important not to have to carry anything unnecessary. But since I don’t share photos of my kids, it’s an excuse to share at least a couple of cute photos.)

- Take screenshots of troubleshooting pages in Loopdocs before leaving so that I have that information in case I need it. This came in handy on a trip once when I had a lot of red loops.

- It saves time and phone battery to weigh things ahead of time and put the measurements in my food app in advance as custom foods labeled with the trip name (e.g., “[trip name] oatmeal day 1.”) I once tried writing the carb count on the individual meal bags, but too much of the writing rubbed off in the packed-full food bag, and I also couldn’t prebolus for breakfast when the record of the carb count was 10 metres up in the air. (Food is hung up overnight in the backcountry so that bears are less likely to be able to get at the food bag.)

Biggest Bang for the Buck

Shorter version: My top three T1D management techniques that give me the most benefit for the least effort required are: drinking lots of water, getting daily exercise, taking fast-acting insulin a specific amount of time ahead of eating. (next section)

Longer version: I sometimes joke to myself that I have three major priorities in my life (my family, my research & students, my health) and time for about two-and-a-half of them. My sad “joke” reflects the reality that I have to fit T1D and its many demands on my time alongside other things. So when I am going through especially busy, stressful times, I have learned that it is useful to focus on the things that give me the biggest bang for the buck when it comes to my health. By that, I mean that even though there are many things I might do with unlimited time, with constraints on my time and effort, I want to use my time and effort as efficiently as possible. Starting with the biggest bang for the buck, the things that I have found most helpful to me and my T1D are:

- Drinking plenty of water (time/effort: low, benefit: high)

- this is by far the thing with the greatest benefit for the least effort

- Getting physical activity every day (time/effort: high, benefit: very high)

- anything is better than nothing, but I only notice benefits to T1D if I get at least 30-60 minutes a day (hence high time/effort required)

- outdoors is best for mental health benefits

- Taking insulin at the right time (time/effort: moderate, benefit: high)

- multiple daily injections (MDI): taking long-acting at a consistent time each day (setting a reminder alarm if needed or attaching the habit to another time-based habit)

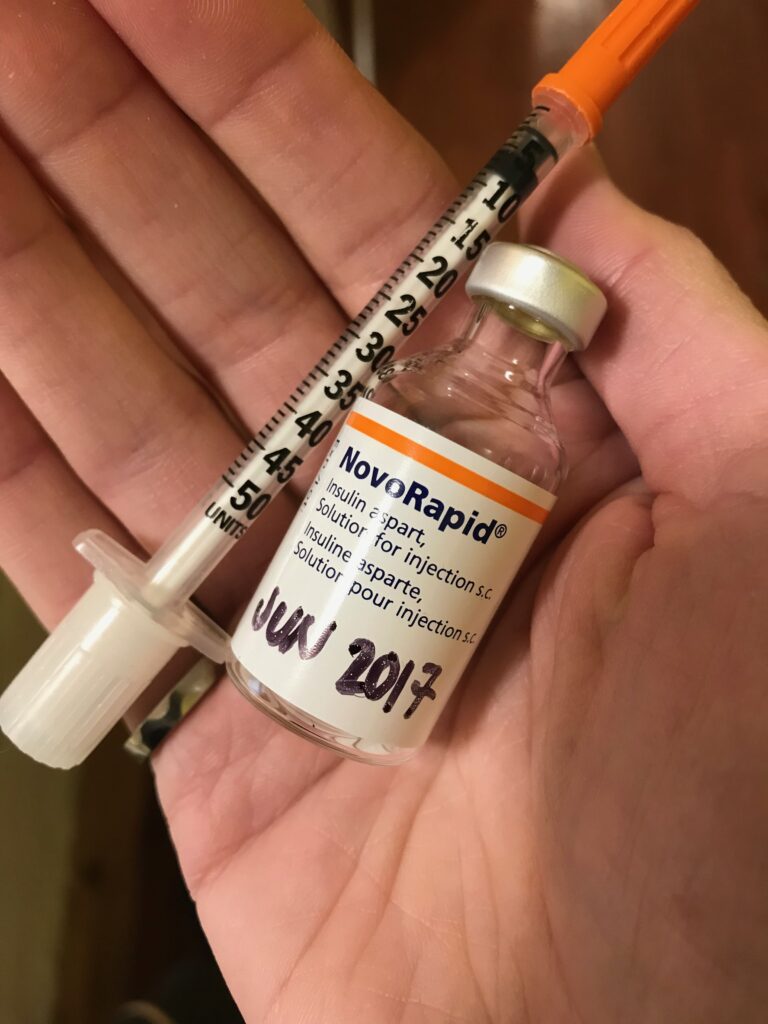

- pump & MDI: prebolusing 10-30 minutes for food (prebolus time may vary … for me, Fiasp takes 10-12 minutes, NovoRapid takes 30 minutes)

- Eating lots of fibre and protein (time/effort: moderate, benefit: high)

- fibre and protein really smooth out the way food absorbs, and they also help me avoid stress-eating too many carbs

- Sleeping decently (time/effort: high, benefit: very high)

- I need 8 hours but if I can’t get that much, some is better than none

- naps count as sleep

- when we had infants & toddlers (especially our first, who was not a good sleeper) my husband and I each had a predetermined 4- to 5-hour sleep window that the other person worked hard to protect

- Eating things that are somewhat predictable for me so that I can better match insulin to food (time/effort: moderate, benefit: moderate)

- figuring out a few reliable meals has really come in handy during times when I needed to simplify things

- here’s a list of things/recipes I like for anyone who would like to peruse for ideas

- Checking BG before and 1-2 hours after eating (time/effort: high, benefit: moderate)

- a CGM makes this easier, but I did it for many years with a meter

- Doing something for mental health (time/effort: high, benefit: moderate)

- physical activity and sleep can overlap with this, but sometimes I need to do other things for mental health

- Having routines & rituals (time/effort: very high to develop but low to maintain, benefit: moderate)

- I am a success-begets-success person, meaning I do better when I feel like I’m not a failure

- maintaining little routines & rituals makes me feel like a success at self-care, which makes it easier for me to tackle other, more time-consuming T1D tasks

This concept of focusing on the biggest bang for the buck also applies outside of T1D for me. For example, if I’m not feeling very energetic and I haven’t been sleeping enough and getting enough exercise, I focus on meeting basic recommendations for exercise (150 minutes/week; see also US guidelines) and sleep (7-9 hours a night) for at least a week or several before I start to consider other possible issues.

Burnout

Shorter version: I’ve gotten through burnout by riding it out as best as I could, and not beating myself up over it. (next section)

Longer version: When I’ve gone through periods of burnout, what helped me most was:

- accepting that my motivation was low at that time and not getting upset with myself about it,

- focusing on the basics: always taking insulin, testing at least twice a day (once I had a CGM, this became wearing the CGM), going for walks outside if possible,

- simplifying diabetes and life as much as I could in the current circumstances,

- getting extra sleep if I could, and

- repeating favourite meals and snacks over and over.

The repeated meals and snacks provided both comfort and predictability. I repeated meals and snacks that satisfied three criteria: 1) I like it, 2) I can afford it, and 3) I know how to bolus for it (or I can probably figure it out without too much effort.)

I am grateful that I haven’t had diabetes burnout in a long time, but I have definitely had times more recently when diabetes on top of everything else I was managing felt like a lot. Having some basics on which to fall back was really helpful in those times.

Comfort In, Dump Out

Shorter version: Sometimes, caregivers need a listening ear. In my view, ideally, they will seek that from someone other than the person with T1D. Based on my experience as a child, I would especially recommend that parents not complain to their children about how hard the child’s T1D is on the parent. Tell someone, but make it someone other than the child. (next section)

Longer version: One of the most helpful distillations I ever encountered about how to talk with people with health conditions was this article about what the authors called the Ring Theory. It is focused on traumatic acute health events, not chronic illness, so it doesn’t apply perfectly to my own experience of decades with T1D with their waxing and waning intensity. However, the central idea, “comfort in, dump out,” is a very succinct summary of how to deal with a wide variety of difficult health situations, including my experience of T1D. I know, for example, that my T1D occasionally adds stress to my husband’s life that he would not experience if I hadn’t brought my confused immune system to our relationship. While I acknowledge that my T1D has an impact on him, if he needs to vent to someone about that, it is better (for him and for me) when he seeks a discussion with someone who is not me; for example, a friend, his mom, another partner of an adult with T1D, or the like. The phrase, “comfort in, dump out,” has been a helpful way to succinctly convey this idea.

Complications

Shorter version: Human bodies are not made to last. T1D can wear our bodies out faster, and, as much as I hope my good adult BG control will help me, it can only do so much, especially given my childhood management. I find this to be an especially hard lesson to absorb, but there it is. (next section)

Longer version: If I go by definitions in scientific papers (for example, publications from the Joslin medalists’ study), I have no complications. My kidneys and heart are in great shape, I have no neuropathy (nerve damage), and no proliferative retinopathy. I feel really grateful for that, especially given the sub-par management during my childhood years. I also note that a lot of the science on complications of T1D suggests that while blood sugar management can help reduce risk of complications, the biggest predictor of complications is how long a person has had T1D. This is sort of like how age is the biggest predictor of things like cancer, heart disease, and other conditions. In other words, tighter blood glucose management may delay the onset of complications but if I live long enough, may not completely prevent them from ever happening. I’ve also seen science suggesting the variance attributable to glycemic indicators is lower than the variance attributable to genetic factors. In plain English, although I can (and do) do my best, the science that I have seen suggests that a good amount of whether I end up with complications comes down to how long I live, combined with the genetic lottery and the overall randomness of life. So I feel lucky thus far.

Although I don’t have any complications according to the above definitions, there are issues I have experienced or developed over time that I probably wouldn’t have or wouldn’t know about if I didn’t have T1D. The biggest issue that affects my life in a meaningful way is that I’ve had hypo unawareness for many years. I typically have no detectable hypo symptoms until I am truly, dangerously low. It usually isn’t until around 2.6-2.9 mmol/L or 47-52 mg/dl that I start to feel something. I have been told that this is likely linked to the repeated, severe hypos I had as a child. I deal with my hypo unawareness by using a continuous glucose monitor and being really careful, especially if I need to drive or travel solo. (Also see the section titled Hypos.)

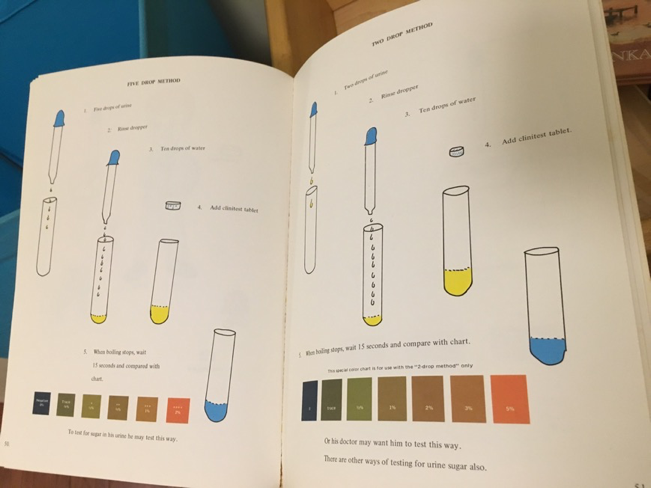

I also just got my first diagnosis of mild nonproliferative retinopathy (formerly known as, “background retinopathy”) recently, which threw me, even though it probably shouldn’t have. I know that this is extremely common, especially for those of us long-term T1Ds diagnosed in the era of urine testing and NPH insulin. It is so common and such a non-issue that, in studies of people with long-term T1D, the analyses often lump all the least-affected people into one category, combining mild nonproliferative retinopathy and no retinopathy together. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (which studied people diagnosed before or around the same time as I was) reported that 97% of people with T1D had at least a little bit of retinopathy after 25 years, so I feel fortunate to have made it to 40 years. (I still preferred the comments, “Are you sure you’re diabetic? I can’t tell from your eyes!” I got for 39 years.) I’ve since had follow-up testing to confirm that it’s extremely peripheral, so that’s good news, because as long as it isn’t progressing, it is very unlikely to ever be a problem, and may well never need treatment. The retina specialists also noted that they’re only able to detect it thanks to advanced testing methods. (“If we were using the technology we had 10 years ago, we wouldn’t have found this.”) Hopefully I will be like most people diagnosed at this point: it will remain stable, I won’t need any treatment, and it won’t progress beyond a little bit at the edges. If I’m in the minority of people who do need treatment at some point, the treatments available these days are very good, and have greatly reduced the number of people who will experience vision loss compared to previous generations of people with T1D. My husband also pointed out, “We’re not built to last forever,” which I found oddly comforting.

And yet, this news still gave me the chance to learn some more about living with T1D. All my life, I’ve heard statements about, “the complications that will happen if you don’t take care of yourself.” I’ve never loved that expression, because it propagates the myth that diabetes complications are meritocratic—that the only people who end up with complications “deserve” them. (This is similar to how people with type 2 diabetes are often blamed for their condition, with little to no acknowledgement that we are not all dealt with the same genetic hand and, thanks to different conditions of life, we are not even all playing the same game.) On top of that preexisting dislike, it meant that when one of the scary complications finally made a little crack in the thick barrier I’d carefully constructed and defended over decades, I felt betrayed. I’ve taken excellent care of myself for many, many years. It was especially hard emotionally because my childhood management was not great, and if there’s a causal relationship at play here (rather than just the random nature of biology or genetic luck) the medical neglect I experienced during childhood is most likely what kicked off a slow progression that brought me to now. So I feel sad about the support I needed but didn’t get as a child. It’s also possible that my hypo unawareness (also linked to my childhood management with its repeated severe lows) may have contributed to this diagnosis, as low blood sugar can contribute to eye damage among people with diabetes.

In any case, the main thing I learned from this news is that it is useful to allow myself to feel the feelings I have, to reach out for help when I need it (many thanks to the colleagues who helped me put the news in perspective) and to avoid getting too cocky about excellent blood glucose numbers. There are still no guarantees.

Consistency

Shorter version: Consistency beats perfectionism every time. The only things that have ever helped me in T1D management are the things I can do consistently. Burning myself out in fruitless attempts at perfection has never been useful. Being consistent requires being realistic with myself. (next section)

Longer version: I don’t know if there is research on this, but anecdotally, it seems that perfectionism is common among people managing T1D. I wonder if part of it comes from being repeatedly invited to reflect on your mistakes. I have definitely had the classic experience in which a health professional points to a BG from last month, and asks me, “What happened here?” I suspect that for those of us with a preexisting tendency towards perfectionism (also known as: a fear of never being good enough), those well-meant interactions may have created unhelpful thought patterns.

Whatever the cause, I have definitely learned over the years that T1D perfectionism is not helpful to me. Consistency, on the other hand, is extremely helpful. Consistency requires me being realistic with myself about what I can do on a regular basis. It also means I have to face the fact that I am overly fond of novelty. I deal with my desire for novelty by (a) running small experiments that make the same-old-same-old feel at least vaguely new and (b) being middle-aged and recognizing that this is part of life.

Control

Shorter version: BG control is possible. It does not guarantee control over all outcomes, but it does make life easier in the short term. (next section)

Longer version: Probably the hardest lesson of T1D (and one that I seem to have to re-learn every so often, see my note above about retinopathy) is that I can do everything “right” but that does not guarantee I will get the results I want. I only control my efforts. I don’t control the outcome.

That said, I’ve definitely learned over the years that blood sugar management is possible. If my current approach isn’t working, I change my approach. I am always confident that a solution exists, even if I haven’t found it yet. I’m not always very happy about it, but I’ve learned over the years that sometimes, the only way out is through.

Working towards BG control is worth it to me because having reasonably level BGs feels much, much better to me than bouncing around. Bouncing around really drains my energy. The energy boost of staying level is extremely noticeable. When I got my first pump and could fine-tune my basal insulin to suit my body’s needs, I once said, “If this is what nondiabetic people feel like all the time, they should be doing more with their lives!”

Daily Kit

Shorter version: It cuts down on my packing time and decisions to have a small pre-packed kit that lives in my backpack. I also have a small number of bare minimum essentials I take with me everywhere, tucked in a pocket or purse. (next section)

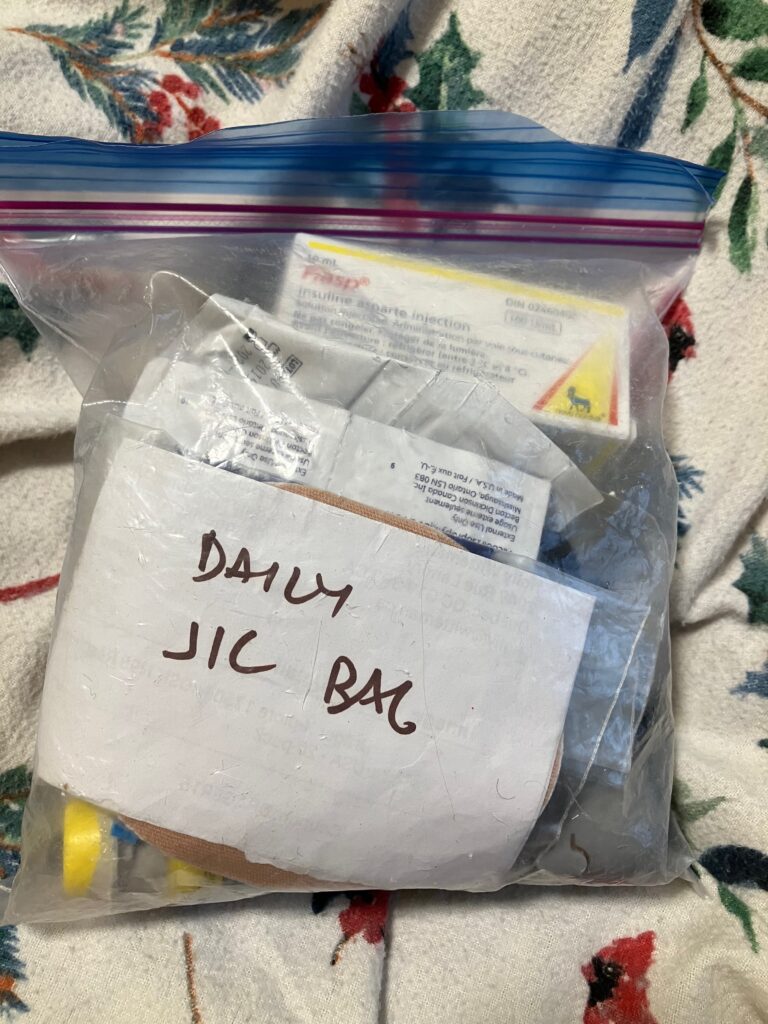

Longer version: I have always found it useful to keep a daily “just in case” kit in a small ziploc that goes everywhere with me. Back in the day, if I was going out for the night, the absolute bare minimum supplies would go in my pockets or purse (glucose tabs, test meter, some strips, a lancet, pen or a vial of insulin and syringe.)

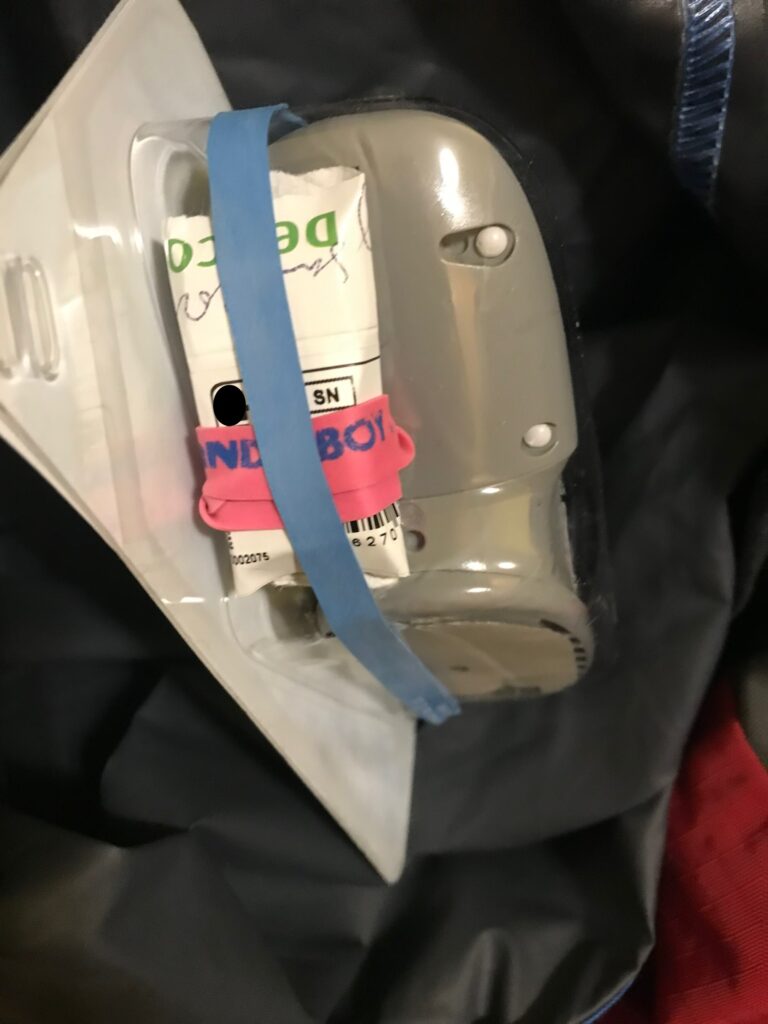

My current usual daily kit has a spare pump battery, a syringe or two, my current vial of insulin (unless I’m going out in very cold weather) with cartridge pieces in the box, a spare linking device to connect my pump to my phone, inhaled glucagon, one or two infusion sets, a sticker to go over my dexcom, some alcohol swabs, a nickel (for removing pump caps), and a bit of cash (just in case.)

Data & Reports

Shorter version: Reviewing my continuous glucose monitor patterns once every week or two is a really helpful habit for my T1D management. It is very easy now that I can check the Clarity app on my phone. I almost never looked before, but now it’s an easy weekly habit. (Thanks for making it available on my phone, Dexcom engineers.) I look at my average BG, standard deviation, Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP), and sometimes my Overlay and Compare report. (next section)

Longer version: I am so happy that Dexcom put their Clarity reports into a smartphone app. Prior to that, I knew that looking at my data regularly was a good idea, but outside of pregnancy, I had never been able to prioritize it as a regular habit. Now that I can quickly pull it up on my phone, I have found that glancing at my data at least once every week or two helps me quickly identify anything that might need tweaking. I usually look at the Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) for the past 14 days, and sometimes the past 7 days if I’ve had a recent change and want to see how it’s going. I also like the Overlay report, because I can look at each day, and the Compare report, because it’s helpful to see if a change I made is having the desired effect or not. I have learned a few useful tricks about using the Clarity reports from the free webinars that Dexcom Canada put out with some experts I know and trust.

I wish they hadn’t dropped standard deviation from the AGP, but at least you can still see it in the Clarity app’s Summary page. I think standard deviation is an underused summary statistic, possibly because too many people don’t understand what it means. Standard deviation is an index of dispersion. In plain language, if you’re looking at your BGs over two weeks, standard deviation shows how far your BGs are from your average across those two weeks. A bigger standard deviation means you have more BGs far away from your average. A smaller standard deviation means your BGs are clustered closer to the average. I’m always happy when my standard deviation is 1.7 mmol/L or lower (31 mg/dl or lower.) The one thing I am careful about when looking at my standard deviation is that, for example, if I have a day running high and then a day running low, the 2-day standard deviation will be similar to what I’d see if I’d spent two days bouncing from high to low, but the solutions to those two situations are likely very different. Summary statistics only tell part of the story. I always look at the graphs as well as the summary statistics. (This also applies to data in my job. I sometimes show students Anscombe’s quartet when they have failed to plot their data before running summary stats. The Datasaurus dozen is also a very funny illustration of this issue.)

Back before I had a CGM, the one time I looked at my data regularly was during pregnancy. I used to pull out my finger prick BG data from the database and built a script that organized it into a spreadsheet by hour of the day. It helped me see patterns that I might not have noticed otherwise. I suspect that many meters now do that on their own with no need to write a script. Knowing what I know now, if I wanted to review the data I had available without a CGM, I would again find a way to review multiple days on a timeline to look for patterns, and I would also keep and review notes a little more aggressively than I do now.

I still have not gotten around to setting up Nightscout again, but I keep meaning to do that. If I were starting from scratch these days, I would use either Nightscout or Tidepool.

Energy Up Front

Shorter version: I find it easier to put in effort (energy) ahead of time to avoid having T1D suck energy from me. (next section)

Longer version: T1D is going to take some of my energy. There’s no getting around that. It just is. The reality of the condition is that it takes energy. My choice is: do I deliberately spend the energy up front to manage my BGs, or do I let my BGs bounce around, sucking energy out of me? I do not love my options here. I would rather not have this condition withdrawing energy from me. But since it’s here and I can’t do anything about its presence, I choose to put in energy up front. This includes doing things like weighing food so that I can set it & forget it with my boluses, planning exercise into my day, choosing mostly food that works well and/or has a predictable impact on my BGs, and so on. I wish I could just live a spontaneous life and not have to spend energy on T1D, but that is not an option on the table for me. T1D is going to take energy, no matter what. The only choice I have is whether I put the energy in up front, or the energy gets sucked out of me later. So I choose to put energy up front.

Fibre

Shorter version: Fibre is really good for everyone, and has extra benefits for those of us with T1D. Eating ~40g/day helps me keep my BGs level. When I had to eat low fibre for a week recently, my daily fibre intake dropped by 74% and my insulin-to-carb ratio increased by almost exactly the same percentage (70%), even after accounting for subtracted fibre grams. I get the best results when I subtract 50-100% of the fibre grams from the carb count, depending on what kind of fibre it is. (next section)

Longer version: Fibre is really good for most people, not just those of us with T1D. It is specifically recommended to help prevent heart problems (extra important with T1D), many cancers, especially colorectal cancer, and, relevant to those of us with any type of diabetes, blood glucose management. As I understand it, it is not only that fibre itself doesn’t get digested, it also prevents the BG effects of a portion of the non-fibrous carbs and fat. I think of this as fibre sort of soaking up some of the carbs and fats.

I had the chance to personally observe the benefits of fibre for blood glucose management recently when I had to follow a low-fibre diet for a week to prepare for my first colonoscopy. I typically eat very high fibre. My average is 40g/day, which is smack in the middle of the recommended amount for people with diabetes (link in French) where I live. When my daily fibre intake dropped by 74% for a week, the insulin my body needed per gram of carbs increased by 70%. This included foods like a particular kind of yogurt (with zero fibre) that I eat all the time, so it was extremely clear exactly how much my insulin-to-carb ratio had changed. I had not fully realized how much I was reducing my insulin needs just by routinely eating high-fibre foods.

When I’m not preparing for cancer screening, my family and I eat a lot of beans, lentils, fruit, vegetables, and whole grains. As I understand it, the reason fibre helps with blood glucose management is twofold. Many people with diabetes are taught that not all of the fibre will convert to glucose, so you need to subtract fibre grams when counting carbs. But in addition to that, fibre slows (and may prevent) some of the whole meal’s conversion to glucose, meaning the whole meal takes longer to digest and may not hit as hard overall. For example, I made black bean brownies recently using 4 cups of cooked black beans across 16 brownies. Sixteen brownies made for four meals’ worth of desserts for my family of four. Observing the effects across four meals, I found that having them for dessert with some berries reduced the impact of the whole meal on my BGs by about a third to a half.

In general, for any meal with a decent amount of fibre (which is most meals for me), I know to expect gentler, slower digestion, and also to subtract 50% to 100% of the fibre grams from the carb grams. I first learned to always subtract 100% but I have learned over time that this is too simplistic. The percentage depends on whether the fibre is mostly coming from insoluble fibre (e.g., whole wheat bread, brown rice), in which case I may subtract up to 100% of the fibre grams, or whether it’s coming from soluble fibre (e.g., chia seeds, oatmeal, lentils) or mixed foods (e.g., most beans, nuts, fruits), in which case I subtract 50-75% of the fibre grams. This is not an exact science, and if I have a mix of fibres, I just guess partway between fully and partially subtracting them. These are not incredibly large differences, so I don’t worry too much about getting it perfect. For example, if I’m eating a meal of 60g carbs with 8g fibre, bolusing for 52g, 54g, or 56g carbs is not wildly different.

Finances & Insurance

Shorter version: T1D is expensive, including in Canada. It is in the interests of insurance companies to make us give up. I have learned I can minimize my out-of-pocket costs by keeping a spreadsheet, a file of notes (with dates of calls and whom I spoke to), and being persistent. (next section)

Longer version: Health care in Canada is sort of public. Things that happen in hospitals, doctor’s offices, and other publicly-funded health care spaces are typically funded by taxes. Things that happen at home (i.e., almost all of T1D management) are only sometimes funded by the public system. What is funded or not funded varies by province. (The way I typically explain Canadian health care to people in the US: each province/territory is basically a big HMO for its residents. If you’re interested in more details, here’s a paper I co-authored that describes the system briefly under the subheading “Canada’s healthcare system.”) Most people have “extended health benefits” (insurance) through work or school to cover things like medications and devices. Throughout my life, I have been in a variety of different situations, from having lots of extended health benefits to none. The most useful things I have learned over the years with respect to finances and insurance are as follows.

I find it useful to keep a spreadsheet of insurance claims. My spreadsheet has service date, date submitted, what it was for, date of the photo or document scan (so I can find it in my files if need be) and then several columns for how much I got back, and follow-up actions taken (e.g., calling the insurance company, submitting the uncovered amount to my husband’s insurance, etc.)

Insurance companies count on you giving up. If you give up, they win. If you don’t give up, you may win. When I was a graduate student, the insurance company that covered graduate students told me our plan would cover 80% of an insulin pump, so I went ahead and got one, only to have them then say I had misunderstood and they weren’t going to cover any of the $6000 cost. I spent hours and hours and hours on the phone over months. It was so frustrating and exhausting. I finally got them to pull the recording of the call in which I was told it was covered. They paid $4000. I did not enjoy being out 2k, as that was almost 10% of my annual grad student stipend, but it was better than being out 6k.

I have found it useful to keep a running document of all phone calls and emails. I record the date and time, the name/employee number of the person with whom I am speaking, and a summary of what was discussed. I can pull up that file as needed and refer to previous conversations. I find that after a couple of years with a given insurance company, most of the wrinkles get ironed out, but this document is invaluable in the first few years. My work has changed insurers three times in the last decade. Every time, I had to start over with this smoothing process.

There have been times in my life in which there were programs that could have helped me (e.g., when I had no extended health benefits) but I didn’t know about them and didn’t know to ask. I wish I had asked. Health professionals can often help, other people with T1D are often very knowledgeable, and some of the most knowledgeable people about these programs are device representatives, so trying to get get an insulin pump is a great way to find out about different funding programs.

I oriented my career around always having extended health benefits, and being able to budget to pay out of pocket for things that insurance does not cover or does not cover fully. For example, I paid a lot out of pocket for continuous glucose monitor for a long time. I find it frustrating that the various provincial systems have these enormous gaps in coverage, so I do what I can to promote better coverage while also recognizing that nothing is going to change in the short term, so it’s in my and my family’s interests to do what I can to put myself in a position to have insurance coverage. I love my job and I do not regret my choices, but I might be doing something very different if I weren’t extremely aware that I have an expensive chronic condition.

Life insurance is often very difficult for people with T1D to get. I can’t even get supplemental group coverage through my work. Any type of diabetes automatically disqualifies me for coverage beyond 3 years’ salary. In Canada, there is exactly one company that will insure people with T1D: Canada Life. My husband and I have paid for private coverage from them since I was pregnant with our first child. It is a substantial part of our budget, and I somewhat resent that, but I am also grateful that there is at least one insurer.

Highs & Spikes

Shorter version: My favourite way to bring down a high is to take a 50-80% correction and then do something involving large muscles like walking, bicycling, or squats. The insulin will be in there for hours, but the effects of the movement stop as soon as I stop moving, so I can bring my BG down quickly and stick the landing. Similarly, if I’m not able to prevent a spike by bolus timing, I can typically just add a walk after eating. (next section)

Longer version: I am grateful that I rarely have stubborn highs these days. (Thank you, Loop.) But I’ve had them at times, and the best approach I found for bringing them down has been: if there are ketones, I follow a ketone protocol. If I don’t have ketones, I take a correction, drink 500mL to a litre (2 to 4 cups) of water, go for a walk, ride my bike slowly, or, if I’m really crunched for space or time, do squats. Any movement speeds up insulin action, but using large leg muscles is especially good.

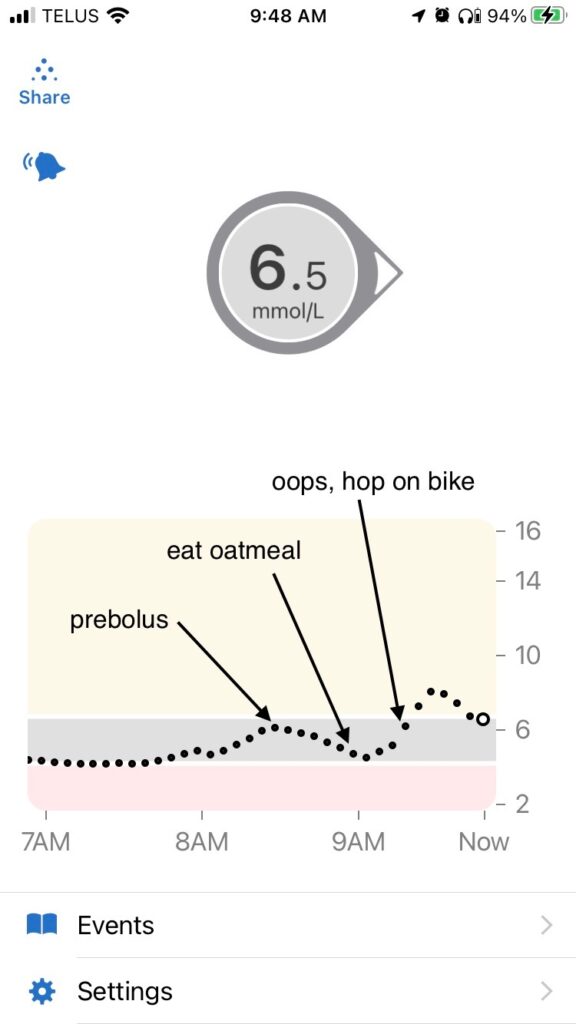

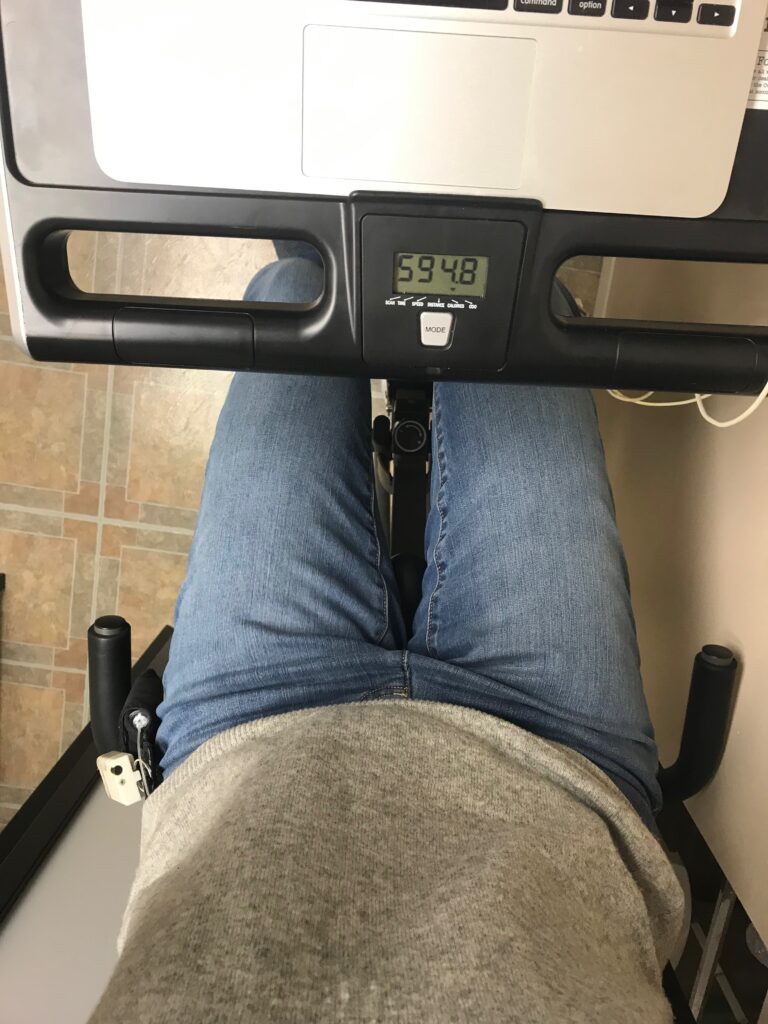

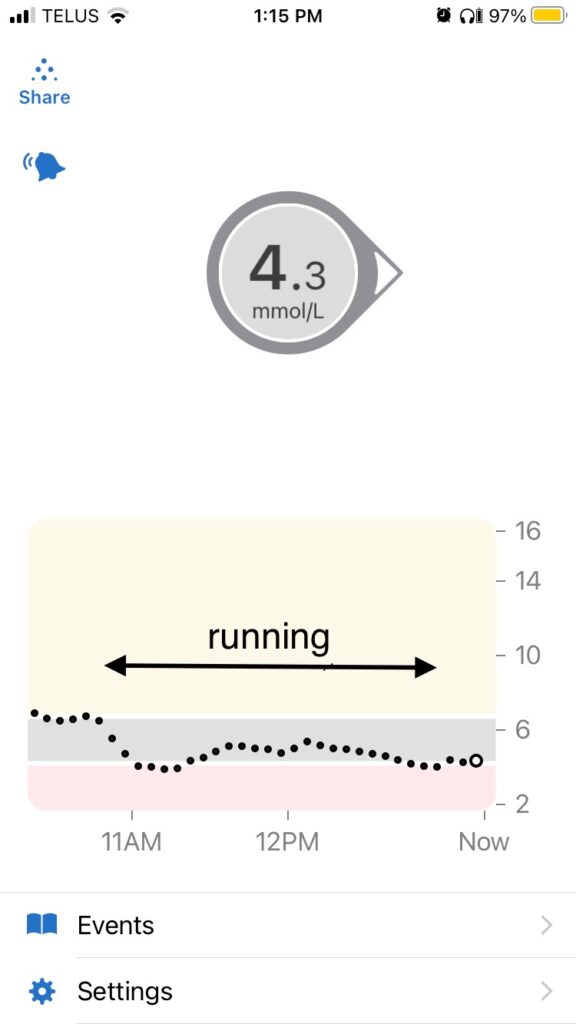

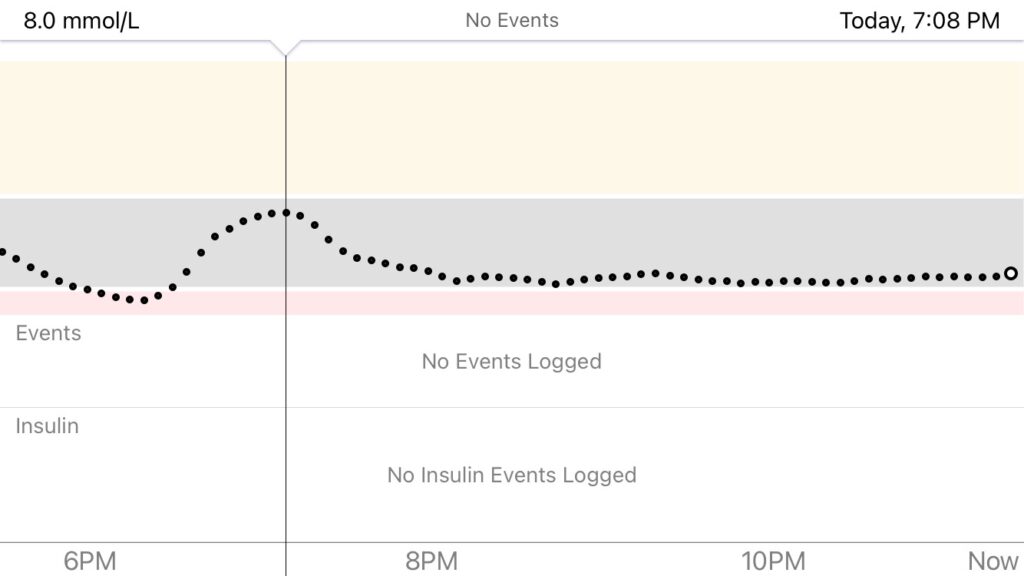

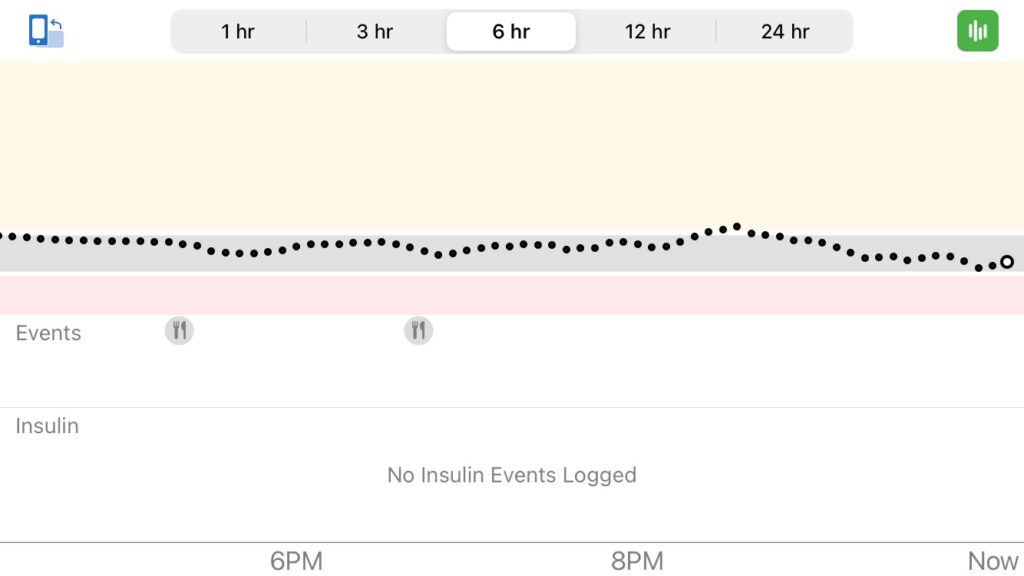

I use a similar approach for blunting spikes. For example, if I am not able to prebolus for some reason, or if I make a mistake in how I plan a bolus, I can often correct it afterwards by adding a bit of activity. Below is a recent example of what that looks like. I was experimenting with timing high-carb breakfast (oatmeal) on days I don’t run in the morning, and I got the timing wrong, so I fixed it afterwards with a bit of leg movement to boost the insulin, also known as riding-a-stationary-bike-while-answering-emails. Before I had the bike option, I would have used walking or squats instead. I can also answer emails on my phone while doing squats. #BizarreAcademicSkills

For folks in countries that use mg/dl:

10 mmol/L = 180 mg/dl

6.5 mmol/L = 117 mg/dl

6 mmol/L = 108 mg/dl

4.2 mmol/L (bottom of my range) = 76 mg/dl

What I especially like about using a combination of insulin and activity to deal with highs and spikes is that, unlike insulin, activity starts working immediately as muscles suck up glucose, and its effects stop very quickly when I stop moving. There is some residual increased insulin sensitivity after a lot of activity, but I’ve never had light walking, biking, or squats do anything to my sensitivity after I stopped moving. In other words, while I can sometimes overshoot (pun intended) when using insulin alone to treat a high or spike, I can be more precise when using less insulin combined with some activity. This allows me to bring down higher BGs faster without going low.

Hypos

Shorter version: My best way to avoid hypos is to avoid needing great big correction boluses. Looping is a huge help. The fastest hypo treatment for me is sweetened chalk glucose tabs. (next section)

Longer version: I’m completely hypo unaware and have been for almost two decades. I’m told that this is likely linked to my frequent severe hypos as a child. One of my main repeated childhood memories is coming to consciousness, vomiting from the glucagon, and then spending the rest of the day throwing up. Fortunately, I haven’t needed glucagon as an adult, but in the years before I got a continuous glucose monitor, I did have two severe hypos, one while 14 weeks pregnant with my first child and one while traveling solo. A few years ago, I also started having really unpleasant post-hypo hangovers in which I am intensely, unshakeably sad for several hours after a hypo. So I am really motivated to avoid hypos in the first place and to treat them as quickly as possible when they happen.

I find that the best way to avoid hypos is to avoid highs. It sounds bizarre, but by doing things to avoid going high or treating a rise as quickly and early as possible, I don’t accidentally overtreat the high because my absorption was different, my sensitivity was a little off, or something else went pear-shaped. Loop (see section: Looping) has helped enormously with this. It basically automated and refined what I was already doing.

For treating hypos when they do occur, here are my personal observations from many years of experimentation:

- Best for quick recovery: glucose tabs + a drink of water

- Note: Water helps any hypo treatment hit me faster. I was given this tip many years ago by a certified diabetes educator who herself had T1D. If the treatment is a gel of some kind (glucose gel, honey), I find it also helps to put into the pocket of my cheek and rub my cheek from the outside.

- Least likely to overtreat with: glucose tabs, because, unlike my kids when they were toddlers, I will never eat these unless I have to

- I let both my kids try my glucose tabs as toddlers (I made this mistake not just once, but twice!) mistakenly thinking that, once they tasted them, they wouldn’t ask for them anymore.

- There was a time in my life when I just could not choke down glucose tabs anymore and moved to lifesavers for a number of years. Lifesavers were better than nothing but they were not as fast as glucose tabs and I was more likely to overtreat. These days, I am back to glucose tabs as my first choice.

- Best for running: glucose gels

- Most likely to make a gooey mess in my pocket after I forget they are there: glucose gels

- Best for someone else to give me in the night: juice box with a bendy straw

- Best add-on to help avoid repeat lows: peanut butter on: toast, apple slices, or a spoon

- Most enjoyable while treating: cereal and milk

- Most likely to overtreat and regret it later: uh, cereal and milk

Insulin

Shorter version: I have found it helpful to try different insulins, pay attention to how different insulins work in my body (when they peak, how long they last), track how different injection/infusion sites perform, rotate my sites by switching sides each month or each sensor change, and be aware of rules of thumb in the book Think Like A Pancreas by Gary Scheiner. (Click here to jump to a summary of the rules of thumb.) (next section)

Longer version: I have always found it useful to try new insulins when they come out. I am not usually lining up to be the first person in Canada to get the latest vial, but I do like to give new options a try at some point and see if they are better than what I had used before. I started on the old beef & pork insulins (Toronto and NPH), moved to human synthetic insulins (R and N), used different long-acting insulins (Lente, Ultralente), used Humalog in pens, and since I started pumping, I have used Humalog, NovoRapid (also known as Novolog elsewhere), and Fiasp. I am currently using Fiasp. It find it stings a little occasionally, but the speed is worth it. I like that it starts a bit faster. I do not like that my sites don’t last as long. I also do not like that it still lasts 5-6 hours. I am contemplating giving Apidra a trial, as I’ve seen some data suggesting that it can clear faster.

I have found every insulin to be at least slightly different. I need a bit more or less of different insulins, they differ slightly in how long they take to start working and how long they take to clear out of my system. This also varies by how much I take. I find that bigger boluses often seem a bit sluggish to get going for me and then, once they start, they hit hard. But by and large, all the insulins I’ve used in the past couple of decades (Humalog, NovoRapid/Novolog, Fiasp) take about 5-6 hours to clear my system completely. Setting duration of action to be shorter is a recipe for me to have trouble with exercise and insulin on board. So the most useful thing I have learned is: when trying a new insulin, pay close attention to when an insulin peaks, and when it is done working.

I find that insulin action also varies by where I inject/infuse it:

- my most predictable (i.e., least variation from one bolus to the next) locations: on my hips and around towards my back

- my fastest infusion site location: belly (I will also occasionally use my upper abs, but it’s harder to find a comfortable spot there)

- my fastest injection location: legs (this would probably also be my fastest infusion site but I cannot deal with sets on my legs … it’s way too close to muscle for comfort)

I use this knowledge as needed. For example, as noted above, I don’t put infusion sites on my legs because it just isn’t comfortable for me, but last year when I had a site failure and spiked up to 15 mmol/L (270 mg/dl), I grabbed a needle, injected 2 units right next to my quad, and hopped on the stationary bike I use for zoom meetings. My BG was back down within half an hour and I didn’t go low.

To rotate infusion or injection sites, an insulin pump trainer who herself had T1D gave me the tip: pick one side of my body for one month, then the other side of my body the following month. I did that for years. Once I started putting my continuous glucose monitor on my arm, I switched to putting my site on the same side as the CGM instead.

All my amounts and ratios are fairly textbook on the lower end of what’s expected in the standard published formulas. I really, really like the book Think Like A Pancreas by Gary Scheiner, which explains the textbook calculations in detail. (My only problem with the book is its insistence on testing everything on days with no activity, no menstrual cycle, no stressful or exciting events … I end up with no options available!) When I first read it long ago, it helped me understand recommendations from my diabetes care team and helped me speak their language when I explained adjustments I’d made. The key formulas I have found useful are the following. (Note that these use weight in kg. If you use lbs, you can calculate your weight in kg by taking your weight in lbs and dividing by 2.205. This means the number representing your weight in kg is a lot smaller than the number representing your weight in lbs. For example, 150 lbs is about 68 kg.)

Formulae in Think Like A Pancreas, and what I have learned about their accuracy for me:

- Total Daily Dose (TDD) for very active adults is listed as typically 0.4-0.8 units of insulin per kg of body weight. For moderately active adults, it is 0.5-1U/kg. For inactive adults, it is 0.6-1.2U/kg.

- This is accurate for me. I am very active and my TDD runs around 25U on average these days, or about 0.4U/kg.

- That average is very much an average. My actual TDD varies depending on things like activity, hormones, and food. Most days it’s somewhere in the range 23-27U, but in the past year, I’ve had TDDs under 10U (hiking trip days) and almost at 40U (sedentary travel days.) I find it helpful to glance at my TDD routinely so that I have a sense of my normal variation. This helps me see patterns that are unexpected due to hormones or illness.

- Total daily basal insulin for very active adults is listed as typically 0.15-0.4U/kg. For moderately active adults, it is 0.2-0.5U/kg. For inactive adults, it is 0.2-0.6U/kg.

- This is accurate for me. My total daily programmed basal insulin is 0.18U/kg. (My actual basal varies because of how Loop works, but I have tested those basals recently and know they are right.)

- Estimated insulin-to-carb ratio (I:C ratio) is 1 unit to 850 grams of carbs per kg of body weight.

- That’s almost exactly accurate for me in the morning. My I:C ratio is 1:865/kg in the morning. It’s too much insulin for me with my usual way of eating the rest of the day. My I:C ratio is 1:1200/kg the rest of the day.

- However, when I had to eat low fibre for a week, the Think Like A Pancreas estimate was not enough insulin, so I suspect my overall ideal I:C ratio for a more typical diet (given that most people get less fibre than the recommendations but a bit more than a low residue diet) would probably be pretty close to 1:850/kg.

- Estimated insulin sensitivity factor (ISF), meaning how far one will fall after taking 1 unit of insulin, is 94/TDD in mmol/L (1700/TDD for mg/dl), and it’s typically 30%-50% higher (meaning most people need 30-50% less insulin) at night

- This is a bit too much for me, though the 50% less insulin at night is correct. My ISF is 111/TDD most of the day, 100/TDD in the morning, and 143-154/TDD overnight.

When I am testing and adjusting, I keep notes. I am not always great at making the space in my head to remember all these details. Also, given how long I’ve had T1D, it all starts to blur together. So I deal with this by keeping notes. I have done it in a little book, but these days, I use screenshots of settings screens in which I add little notes using the edit image function.

Logging Food

Shorter version: For years, I thought logging food sounded like a pain. But then I was inspired by someone who had lived well with T1D for 70 years, so I gave it a try. It was a bit of work to get started but now it’s just part of how I manage, and it’s really helpful to me at my current stage of life and T1D. (next section)

Longer version: I only started logging food routinely in the past decade. Previously, I had always disliked being asked to bring in a food record to a dietitian consult. I once instead brought in 2 weeks of photos of my vegetable-filled plates. They didn’t ask me for a food log again.

I think because I associated it with being annoyed, I thought of logging food as a pain. However, once I decided to make an effort and got in the groove of it, it has become a quick & easy habit and really helpful for my T1D management.

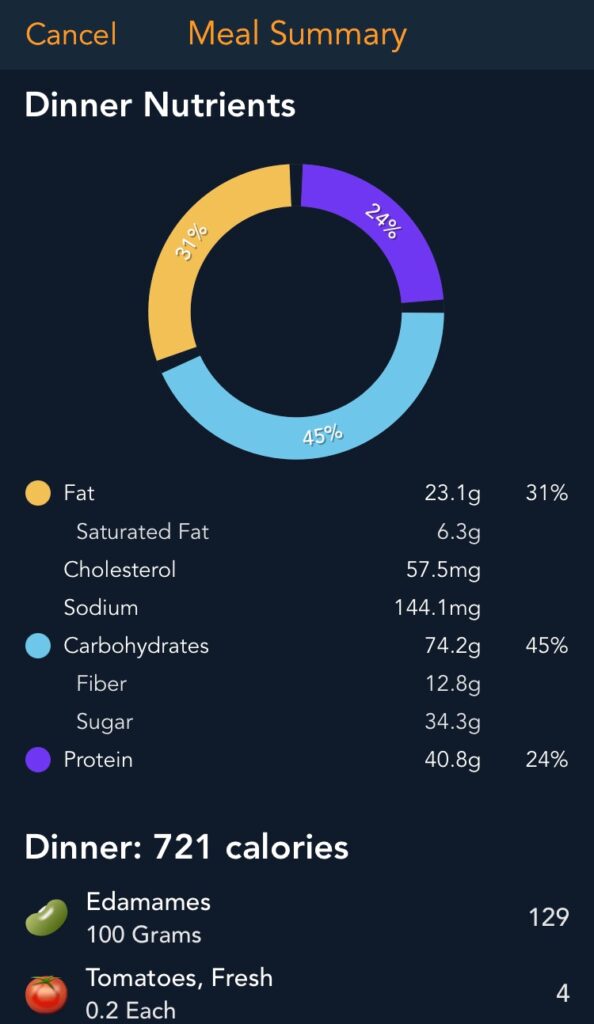

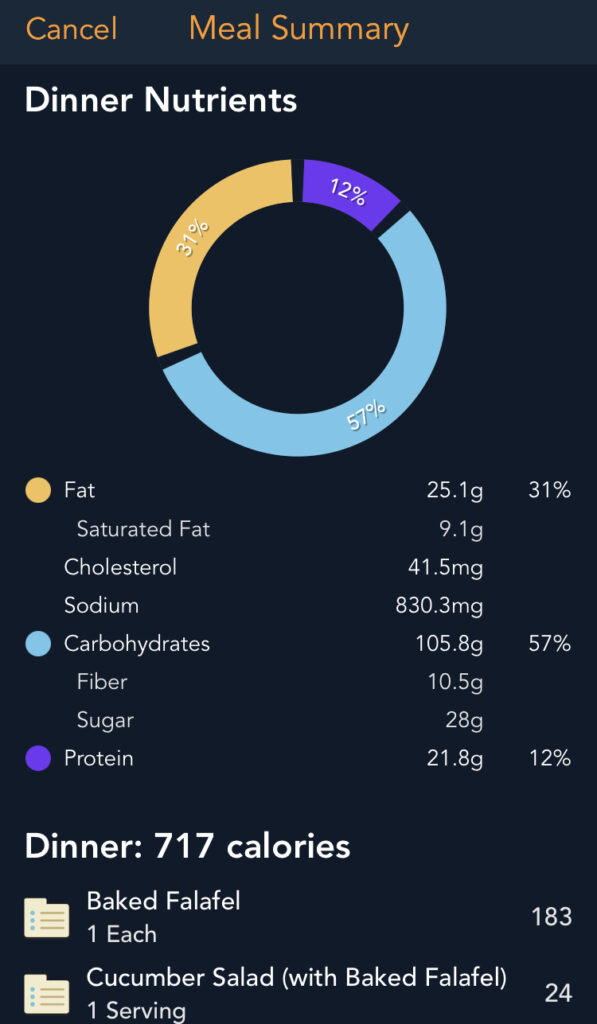

I was inspired by an older gentleman who, when I met him, was 71 years old, had lived for 70 years with T1D, and was in great shape. We were at a multiday meeting together, and I noticed at mealtimes how he jotted down everything he ate in a little notebook. I really liked his attitude and how well he was doing, so I decided to give it a try, and started using a food logging app. I was initially motivated to do it to get more precise carb counts, but I’ve ended up using it for all sorts of purposes—refining fat and protein boluses, figuring out exactly how to modify I:C for fibre, making sure I am getting enough protein, and losing weight when I decided to do that. (See section: Weight Management.)

Logging food can promote disordered eating or disordered thinking about food, so I’m not sure it’s right for everyone. There were times in my life when it would not have been right for me. But it is very helpful to me at my current stage of life. I’m glad I decided to finally start doing it routinely.

The app I use is called Lose It. It was the first one that came up when I searched for a food logging app, all of which seem to be oriented around weight loss. This one looked like it would make it relatively easy to put in my own recipes and repeat combinations of foods so I don’t have to enter everything by hand every time. It’s reasonably easy to use and I really like the ability to call up combinations of foods and recipes I’ve made before. I don’t love all of its features, but it is fine. I don’t know if it’s the best such app, but I’m now committed by the fact I’ve spent years entering recipes and would not want to start over in a new app. (It has an API and I occasionally wonder how much work it would be to port the data directly into my automated insulin delivery system…)

Looping

Shorter version: I use Loop, one of the do-it-yourself automated insulin delivery systems. It has been life-changing. For anyone who can access the tools, I highly recommend trying a do-it-yourself or commercial automated insulin delivery system. Available commercial systems vary by country. Here’s a good write-up with links to the various do-it-yourself systems out there if you are interested. (next section)

Longer version: I started looping (using Loop, one of the three main do-it-yourself automated insulin delivery systems out there) four years ago. Every 5 minutes, the system analyses the estimated blood glucose from my continuous glucose monitor, makes a prediction about where my BG will go based on what I have told it about food and settings and what it can see in my current trajectory, and adjusts accordingly, adding a bit of insulin if I might need a bit more, reducing basal if it thinks I might need a bit less. I can also crank my insulin up or down by a set percentage if I want to. It has been life-changing. I offer my undying gratitude to everyone who has helped to bring these systems to the community. I had very good control before Loop, but Loop has brought me some fantastic benefits:

- fewer lows

- easier time exercising

- uninterrupted sleep nearly every night

- I cannot emphasize enough how amazingly life-changing it has been to be able to sleep through the night almost all the time.

- the ability to set overrides (% increases or decreases of overall insulin) and/or to bolus from my watch

- This is incredibly useful in meetings at work when it is tricky to pull out a phone, when doing things outdoors in cold or wet conditions, or while out bicycling, running, commuting, walking, etc.

- better results and fewer life disruptions for the same amount of effort

- T1D is still a lot of work, but I more often get to choose when to put in the work, and I get even better results than I did before.

- the ability to program boluses in the future

- I always wanted this with unconnected pumps. I tried my best to make do with extended/dual wave boluses, but those boluses still tended to front-load insulin that I knew I wouldn’t need until some time later when the fat or protein started to hit, or the carbs finally broke through the fibre. Being able to program future carbs makes it so much easier to deal with food that digests more slowly due to high amounts of fibre, protein, and/or fat.

I started with Loop because I was already using an iPhone and that’s the system that ran most easily on iPhones. It is possible to loop with other devices, too, and if I had been using an Android phone at the time, I probably would have started with a system that runs on Android. Here’s a good write-up with links to the various systems out there if you are interested.

Looping is not magic. I’m still using exogenous insulin, and I still can’t take it out once it has gone in, but it’s still light years better than before.

Matching Insulin & Food

Shorter version: Learning to better match insulin to food has meant learning more about how my body digests different foods, and how different insulin patterns cover or swamp the blood glucose effects. My best approach for this has been to keep notes, because I have too many other things taking up space in my head to remember things like this. Learning to better match food to insulin has typically meant eating more fibre and/or protein. In some circumstances (e.g., traveling solo) I use low carb to reduce my margin of error. (next section)

Longer version: I have found that managing T1D is basically balancing food & hormones with insulin & activity. There are lots of things that affect blood sugar (more than the 42 in a well-known list in the T1D community that is missing things like fibre, menopause, etc.), but those four are the biggest ones. A huge part of managing T1D for me is matching insulin and food. This can be done by matching insulin to the food, choosing food that better matches insulin, or a combination of the two. I typically do combinations of both, but sometimes I’ll lean on one or the other. If I am feeling stressed, overwhelmed, or am traveling solo, I am more likely to try to eat food that is more predictable for me (i.e., choose food that better matches insulin). At home or when I’m feeling more up for it, I am more likely to try to figure out how to accurately dose the insulin for a given food.

For me, the key skills for matching insulin to food have been figuring out:

- how much insulin is needed for the food,

- when the insulin will hit,

- when the food will hit and how it will absorb,

and timing the insulin amount(s) accordingly. I mostly do this by keeping notes. I wish I could keep it all in my head but I struggle to extract patterns from vague recollections. I’m much better at being systematic, keeping notes, and adding reminders to recipes & entries in my food log so that the next time I eat that food, I will see my note. One of my favourite notes is on a carrot cake with cream cheese icing we often make for birthdays. My note to self, scribbled at the bottom of the page in my recipe book one day after one of my kids’ birthdays, says: “BOLUS MORE THAN YOU THINK.”

For me, the key skills for choosing food that better matches insulin have been:

- figuring out which foods are more predictable than others, and

- knowing which foods will have a slower (but still predictable) absorption similar to an insulin action curve.

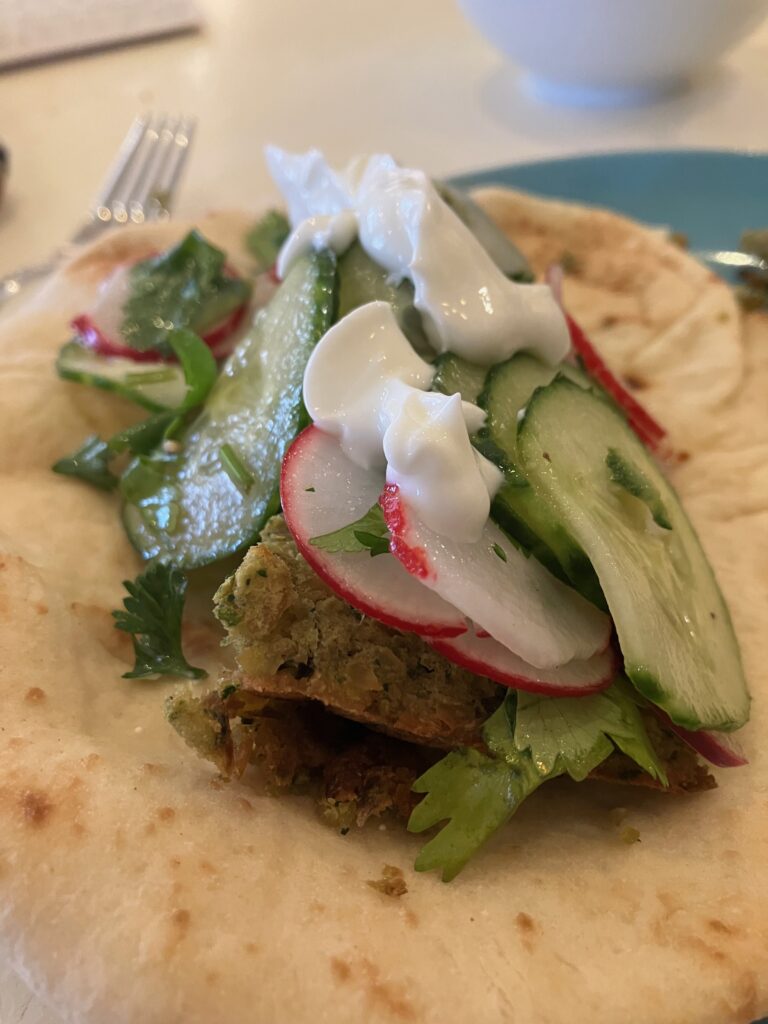

For me, slower absorption usually means more fibre and/or protein. More fat also slows things down, but fat is tricky because it increases insulin resistance and often hits me hard later, so I don’t usually use fat for this purpose. Slower absorption may also mean fewer carbs, though it’s much more common for me to eat things that are high carb and high fibre, like beans, legumes, etc. I do use low carb as a tool at times. For example, when I am traveling solo for work and want to have a smaller margin of error on a restaurant meal, I’ll often look for fish and vegetables on the menu, because those are often available. Some people choose to use this tool all the time. I think that’s a valid choice, and they should be supported by their health care team. I don’t personally want to eat low carb all the time, but I respect the choice among those who make it.

Mental Health & Stress Management

Shorter version: My best lessons for mental health, stress management, and T1D have been that it helps me enormously to: run a lot, do yoga, spend time outside, connect with others with T1D, and sleep. (next section)

Longer version: T1D is hard for a lot of people. I’ve certainly found it hard–more so at times, less so at other times. As I’ve gone through four decades, I have benefited from new management options and learned things that have allowed me to have an easier time, but the neverendingness of T1D is, uh, neverending, and the energy it takes from me at the most inopportune times is always missed. I once read a paper describing a qualitative study of the experiences of younger adults with T1D and was struck by the following two quotes, especially:

“I don’t think people really understand what’s involved. It’s pretty much on my mind the whole time. There’s no day off from it (Female, 30),” and, “It’s a huge thing. But no one can see it so it’s always there and it’s massive for you but it’s invisible for everybody else (Male, 24).”

Even when I’m doing really well at management–sometimes especially when I’m doing really well at management–I’ve learned that I am better on every level when I make time to do things that help my mental health around T1D. The things that help me the most are:

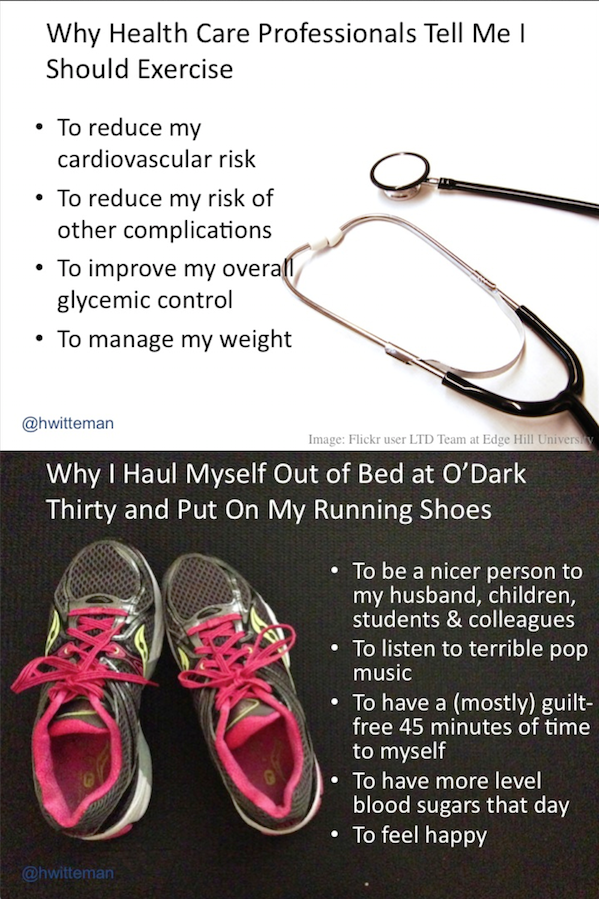

Running. I really depend on running to feel good. I used to do ok running only a few times a week, but I knew it would be good for me to get that boost more often. Some years ago, I worked up to longer distances, 5-6 times a week. It is such a joyful, meditative part of my life now. I don’t race or run with anyone else (except for my dog sometimes, and my dad when we are in the same place.) Running is just time for me. I’m grateful that it is accessible to me.

Daily (or near-daily) yoga. My eldest kid and I started doing 5-30 minutes of yoga together before bed to help my child several years ago, and this habit turned out to also be really great for me. My current endo had once semi-jokingly written ‘yoga’ on a prescription pad when we were talking about the stress in my life as a new professor with a young family. Although I didn’t fill that prescription immediately, I did remember her recommendation. She was right. My kid and I started by doing a 30-day series from Yoga With Adriene on YouTube, and then we just kept going. The daily habit is really helpful to my mental health.

Getting outside. Spending a longer time outside is better for me, but anything is better than nothing. I can usually manage at least a short bike ride (including commuting to work) or a short walk with a colleague, my husband and/or dog.

Connecting (passively or actively) with others with T1D. When T1D has felt like too much, I initially tried keeping its negative mental health impact to a minimum by avoiding thinking about it. This never worked terribly well for me, so I then tried the opposite approach: spending more time thinking about T1D by connecting with others. This works much better for me. Sometimes this connection is active (mostly online but also sometimes offline) and sometimes it’s passive in the form of reading things written by others with T1D or listening to stories on diabetes podcasts. The passive form really serves my introvert tendencies. It has always been helpful to me to get those reminders that others are also dealing with T1D, working at it, and keeping on.

For anyone in Canada: I didn’t know this would be the case when I started writing this post, but, along with a great team of others with T1D and some supportive researchers, I was able to get some research funding recently to create a way for people managing T1D in Canada (themselves, their child, or another loved one) to connect with others in similar situations, life circumstances, etc. Here’s the press release from JDRF Canada (scroll down to the bottom for my team’s project.) We are in the middle of getting this up and running and plan to launch it in fall 2023.

Sleeping. Sleep was always a challenge for me with T1D, especially given I had so many overnight severe hypos as a kid. Being high at night does not make for good-quality sleep, either. I recall when I was younger feeling so incredibly exhausted and drained when I woke up after a night of difficult BGs. I was able to reduce that a lot as an adult, and in recent years, Loop has helped me turn blood sugar sleep disruptions into very rare events. I am also grateful that my husband is willing to provide overnight backup now. Still, life and work responsibilities sometimes crowd out sleep as a priority. I really notice the negative effects on my mental health (and BGs) if I’ve missed sleep to finish a grant, paper, review, student’s application, and so on. I do my very, very best not to sacrifice sleep these days. Most of the time I succeed.

Oops

Shorter version: I use the word “oops” to help me keep my mistakes in perspective and not beat myself up about them quite so much. (next section)

Longer version: Like a lot of people with T1D, I instinctively take it badly when I mess up. If I mistakenly think that I’ll digest something slowly and it hits me quickly, or vice versa, or I underbolus for fat, or I overbolus before a run, or I ignore a pending low that turns into a crash, etc. my easiest, first, go-to response is to get upset with myself. Example:

“WTF how am I messing this up after 40 #%^ing years of this #%^?!”

I’ve learned over the years from talking with others, from reading research, and from just plain trial and error that this response is, to put it mildly, unhelpful.

What is much more helpful is to have some self-compassion. The word I use now to try to evoke some self-compassion in myself is the one I used with my kids when they were small and they fell down, spilled something, or the like: “Oops.” For me, “oops,” carries a sense of, “Hmm, this isn’t quite what I wanted, it’s a mistake, and I’m going to keep it in perspective.” It isn’t perfect, and I still sometimes get upset with myself, but it helps.

What using “oops” is really about is changing the stories I tell myself. I’m not going to pretend to myself that mistakes doesn’t matter to me. My BGs are not neutral data, devoid of valence. Perhaps if I’d had health professionals with different styles over the years, I might have a different factory setting. But as a T1D child of the 80s, I see my numbers as ranging from “good” to “bad.” We can call them “in range” and “out of range,” but I interpret “in range” as good and “out of range” as bad, so changing the words doesn’t change the meaning for me.

Put another way, in theory, I love the idea of seeing my BGs as just neutral data. (And in theory, theory and practice are the same!) But in my real, messy life, I do see my BGs as assessments of how well or poorly I’m doing. I have never been able to talk myself out of this. After trying and failing to shift my reactions, I instead decided to give up and focus on what I can control: the stories I tell myself about what it means. When I say or think, “oops,” I am telling myself the story: ok, this is not what I’d prefer, but neither is it the end of the world.

Outdoors

Shorter version: I have an easier time spending time outdoors when I give a bit of thought to how to keep my diabetes gear and my hands, which I need to manipulate said gear, dry in wet conditions and warm in cold conditions. (next section)

Longer version: I love being outdoors. Spending time outdoors with T1D is easier when I give some thought to how to keep equipment, extremities, and medication dry and at a reasonable temperature. Some things I have found useful that were recommended to me by others dealing with similar issues:

Keeping things dry: In addition to using dry bags when hiking, I use an Aquapac case for my old Medtronic tubed insulin pump when canoeing, kayaking, or spending a lot of time around water. Note that it can reduce flow, so it’s important to keep an eye on that. (Not needing such a case is one of the big advantages of patch pumps, in my view. But the fact that they stay on for 3 days and you can’t go in a sauna is a real turn-off for me, on top of the fact that they are not funded for me where I live.)

Keeping things warm: Canadian-level cold is challenging to electronics (especially glucometers and phones), insulin, and fingertips. I haven’t slept outdoors in winter in a long time but when I was younger, I did things like go winter camping in Saskatchewan with the outdoors club at my high school. (I loved that club so much.) The temperatures went down to -30degC or -40degC at night. At that time, I kept my insulin and meter tucked into my clothes. These days, I’m never out for more than a day. I can get through a day by keeping insulin pump tubing and my spare insulin tucked in a pocket or bra next to my skin. My phone and spare battery go in an insulated pocket in my coat. I used to use hot packs in my mittens, but my Raynaud’s-affected fingertips now get special treatment with these Motion Heat gloves. They are extremely non-free, but have absolutely saved my ability to enjoy winter.

Parenting

Shorter version: Hypo treatments are mom’s medicine; they are not for sharing. I should have stuck to this. (next section)

Longer version: At least when I was pregnant, there seemed a fair amount of medical information available about how to safely have a pregnancy with pre-existing diabetes. But there was almost nothing about how to deal with situations like, “you’re nursing your baby to sleep, which makes your blood sugar drop, and then your CGM alarms right as the baby is dropping off,” or, “your toddler is tantruming and you need to bolus,” or, “you need to drive your kid somewhere on time and you are too low to safely drive.” My kids are 16 and 11 now (fortunately for them and us, neither one has any health issues, despite my multiple autoimmune conditions) and my T1D has definitely influenced my parenting occasionally. Some things I have learned over the years about parenting when the parent has T1D:

Breastfeeding an infant decreased my insulin needs by about the same amount as hiking all day. I needed about about 60% of normal basal, no change in insulin-to-carb ratio. Breastfeeding a toddler decreased my insulin needs slightly, but not nearly as much as when I was the sole source of food. Having a pre-established hiking basal pattern really came in handy when I had nursing babies and toddlers. Still, stashing low snacks anywhere I might nurse was always a good idea.

I should not have let my children try glucose tabs when they were toddlers. I thought that if I let them taste the chalkiness of tabs, they’d never ask to share them again. That was a mistake. I am embarrassed that I made the same mistake twice.

Once kids can speak clearly and know their numbers, they can learn to dial 911 and tell the operator, “my mom is sick and she won’t wake up.” Fortunately neither one ever had to do that, but we taught them how, occasionally practiced, and kept a landline for that purpose.

Once my children were about 4 or 5, it was helpful to teach them to please try not to ask me questions when I’m low. My decision-making capacity completely vanishes when I’m hypo. They don’t always remember, but then, no one always does, not even adults. Knowing that it’s a thing, though, if I say, “I’m sorry, I can’t answer right now, I’m low,” they understand a bit more about what is happening and can be patient, knowing I will be able to answer soon.

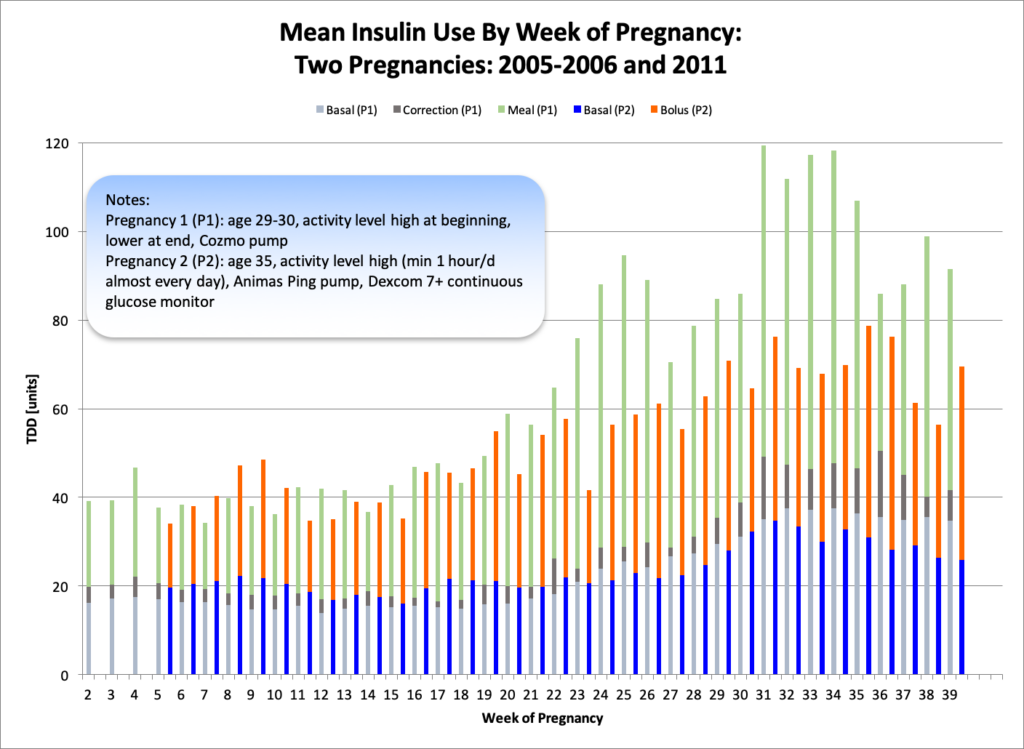

As my kids have grown, I think (hope?) it has helped as I have voiced more of what’s going on for me with my T1D, including giving voice to my emotions around T1D and how I am dealing with them. I hope I am modeling good habits.