I love backcountry camping trips. It is important to my well-being to spend time with lots of trees, water, and few people. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) has always added to the logistical challenge of this need to get away, but I’ve usually managed it somehow, including my most difficult trip with T1D: a backcountry canoeing trip with my husband and 5-year-old, 7 months’ pregnant with my second child. (That was the trip we realized we were going to need a bigger tent than the old 2-3 person Snowfield I’d been taking everywhere since my twenties.)

Since we’ve had kids, trips have typically been by canoe, because it’s easier for transporting small kids. Our eldest even reliably napped in the boat when he was small. It was so great. He would just drape himself over a pack and snooze.

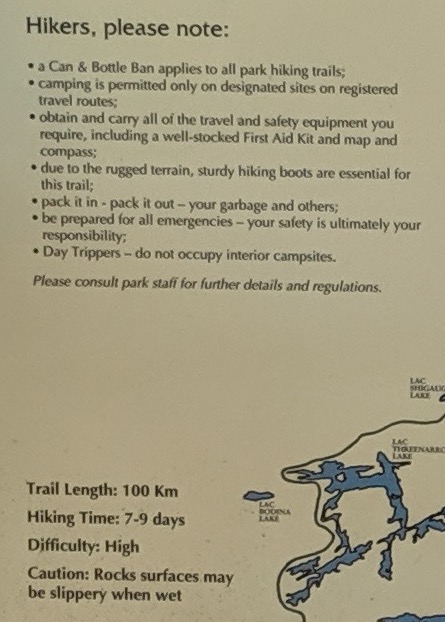

But now our kids are getting older, which opens new possibilities. So this year, my husband and I took our eldest (13 years old) to hike La Cloche Silhouette in Killarney Provincial Park. It is a gorgeous, hard hike. Family consensus at the end deemed it, “tough and awesome.” My husband and I had last hiked the whole thing 14 years prior.

About three weeks before our trip, I started Looping with a form of a do-it-yourself artificial pancreas. Loop is one of the current methods of combining electronics, existing equipment (off label use), and compile-it-yourself code to create a closed loop system that might help lift some of the burden of managing a 24-7 condition that requires relentless, constant vigilance.

Side note: Here’s some official documentation about this approach to self-management from a diabetes org in the UK. As far as I know, no Canadian org has yet put out a statement. I think that statement is pretty reasonable, and I understand why they are worried, but I also think it’s a little disingenuous to express so much concern about dangerous hypos, as if so many of us haven’t already had those without these kinds of devices. Ask any longtime T1D about one of the times they accidentally injected their daily amount of long-acting insulin only to realize it was actually short-acting. For whatever it’s worth, I’ve had far fewer hypos with Loop compared to how many I was having before.

By the time the trip started, I was pretty comfortable with Loop, had nailed down my settings, and was really enjoying it. My favourite part was waking up with reliably great blood sugars every day, no bizarre, ‘What hormones happened overnight?’ surprises. I also liked the increase in time in range along with the decrease in effort required to stay there.

However, I was nervous about being in the backcountry, and couldn’t find much relevant information or tips. (Possibly I didn’t look in the right places. I know that I’m not the only person who has done backcountry trips with such a system. I didn’t have a ton of time to prepare, so I just did my best.)

So, for anyone else like me who is looking for a public information, here’s what I found helped.

Note: This is for a 5-day strenuous trip, in which, if we needed help, it could be expected to be at least many hours, if not a day or more away. There is no phone service even on the long road into the park, though you can sometimes get a cell phone signal on peaks in the Eastern section of the trail.

Note 2: I have high insulin sensitivity and therefore have a low total daily dose (~20-25 units per day) for someone my size (I am tall and stocky) despite eating plenty of carbs (~150g per day on average). As always, YDMV (your diabetes may vary).

Note 3: I’ve lived with T1D for over 36 years now and am pretty good at managing it, thanks partly to having access to helpful technology. However, I had only been looping for a few weeks, so for safety reasons, I was still being very cautious about adjusting settings. I was (and am still) using the main Loop branch and the Dexcom algorithm and app.

MY T1D PACKING LIST FOR REGULAR + LOOPING BACKCOUNTRY TRIPS

Low treatments

- Lifesavers: 2 rolls per day x 5 days = 10 rolls

- Cherry gel: 4

- Glucagon: 2 expired packs (We took expired glucagon because I am tired of paying $100 for stuff that expires the moment you take it out of the fridge. My endocrinologist told me it’s probably fine, and we had the cherry gel as backup.)

Low treatments stay in the tent at night, inside ziplocs inside a dry bag. I know this is not ideal. We’ve had very serious conversations about the tradeoffs between the potential for losing low treatments in the bear hang or being unable to get them in time versus the potential for having an animal smell them in our tent through multiple layers of packaging and human smells. Keeping them close to hand is a carefully calculated risk. (Note that this area has black bears, not grizzlies. We are more conservative in grizzly country.)

We hiked right past a bear on this trip, really bringing this calculated risk home. I didn’t see the bear, but I heard a very clear, ‘get the bleep out of here,’ growl, and immediately afterwards we passed a pile of fresh blueberry bear poop on the trail. We sang, loudly, for the rest of that section of trail.

Insulin

- Regular vial of Novorapid in use (about half full): 1

- Regular loopable insulin pump: 1

- Backup vial of Novorapid: 1

- Backup pen of Lantus: 1

- Backup syringes: 2

- Backup (non-loopable) old insulin pump: 1

Insulin also stays in the tent at night, inside two different ziplocs (one for regular, one for backup) inside a dry bag.

Blood testing

- Regular meter: 1 (charged fully before the trip)

- Regular test strips: 1 almost-full bottle of 50

- Backup regular test strips: 1 bottle of 50

- Backup meter: 1 (with new battery installed before the trip)

- Backup meter test strips: 1 bottle of 50

- Spare Dexcom sensor: 1 (in addition to the one in my arm at the start of the trip, 4 days old)

- GrifGrips: 4 (in addition to the one already on my arm)

Loop extra stuff

- RileyLink: 1

- iPhone: 1

- Screenshots of all the yellow/red loop troubleshooting sections of LoopDocs on my phone

- Apple watch: 1

- Batteries: 3 (plus my husband carried 3 extra, but in the end my 3 were plenty)

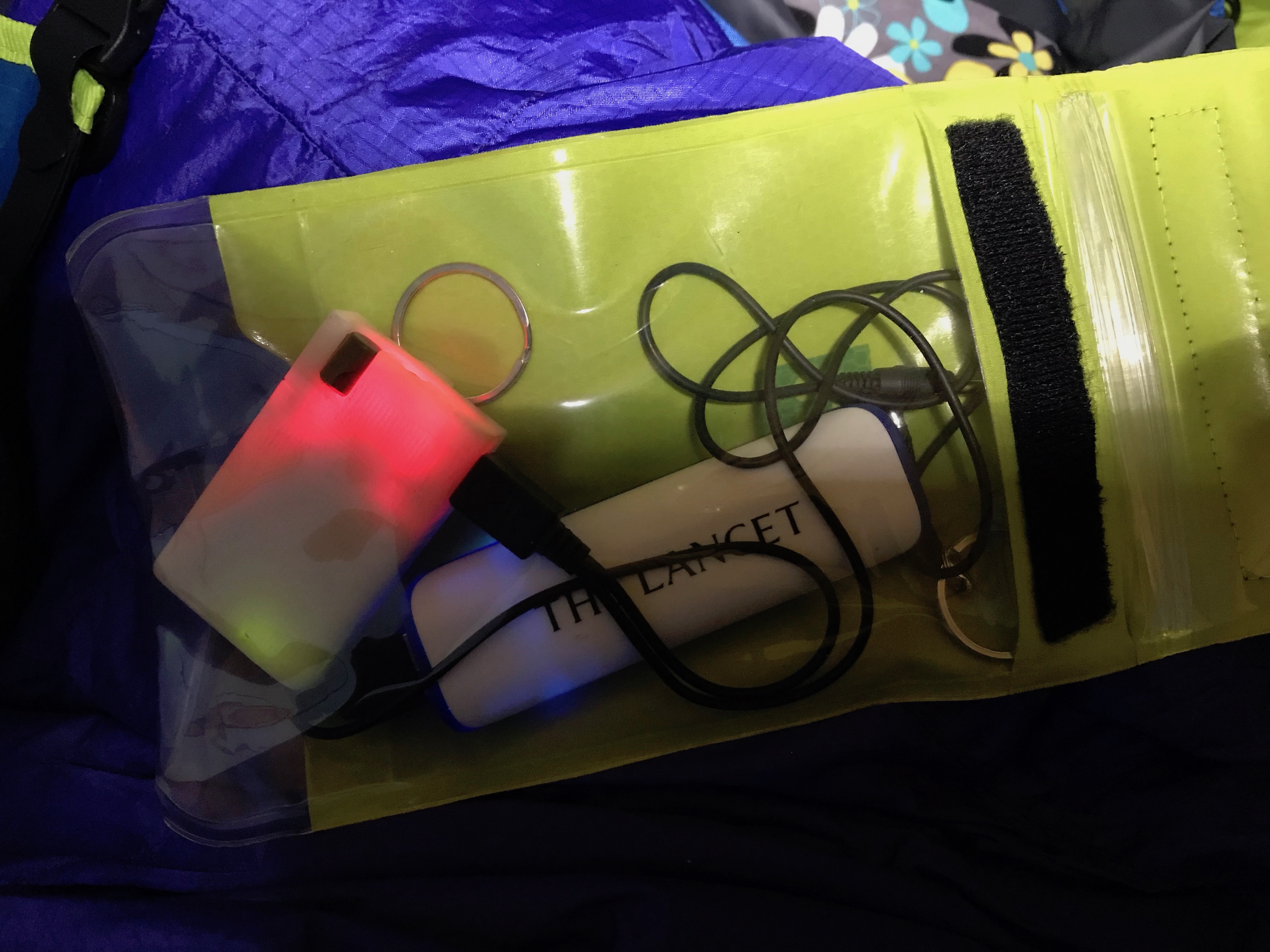

- Power cords: 2 for RileyLink (these would also work for my main meter if needed), 2 for phone (2 cords for each connection type in case one fails)

- Dry bags: 3 (1 for RileyLink, 1 of the same kind for phone, both went inside the larger 3rd dry bag with the pump)

If I were to do it again, I would try to get:

- Backup RileyLink (I didn’t think of this)

- Aquapac dry bag for a tubed insulin pump (I learned about this too late to get it in time)

- Silica gel packs to absorb moisture inside the dry bags–extra insurance for keeping electronics in good shape (many thanks to Greg Axani for this idea)

Also note that nearly half my dry bag of personal gear was diabetes stuff. I did not love this, and if looping weren’t so great and if my body didn’t work better with a bizarre basal pattern that is tough to mimic with long-acting insulin, I would seriously consider going back to multiple daily injections for backcountry trips, since there’s so much less stuff to carry and fewer devices to malfunction and need backups.

Batteries and charging

A key issue in the backcountry is power. The “most people just get into the habit of charging overnight while they sleep” concept is great except if you are sleeping somewhere without electricity. I really hate having lights in the tent, so I first tried charging on the go during the day, but that did not work very well. Day 1 was fine but the cord was old and fraying and when I switched to a more robust cord the cord fell out.

I didn’t love my second choice of charging overnight but that’s what I did, and just tried my best to block out the light by arranging batteries and devices strategically. I wore the watch at night so I could glance at my readings when I woke in the night and charged it briefly at lunch breaks as needed.

I also started by using my flakiest batteries first. The Lancet-labeled battery pictured above is swag from giving a talk earlier this year and it does not hold charge well, so I used it first.

Dexcom sensor startup time

I needed to restart my Dexcom sensor during the trip. (If I didn’t pay so much out of pocket, I would replace at this point, but I reliably get two good weeks out of every G5 sensor, so I cut costs that way.)

I deliberately restarted about six hours earlier than needed so that I could be confident those two hours were unlikely to be problematic. We were up around 5:30 a.m. that day to have breakfast (oatmeal) and get a start on the day’s long hike. I restarted around 9:40 a.m. after I was pretty sure the post-breakfast uncertainty was over and I could tell from the topo map that the next two hours were going to be some of our flattest hiking of the whole trip. (If I did it again, I might look into some of the alternative options, like Spike, that might allow me to avoid the two hour gap, but those two hours were uneventful, so I don’t think it’s strictly necessary.)

Wearing it all

I was very glad to have brought dry bags and to have a watch, because I ended up needing to put the whole assembly (phone, pump, RileyLink) in a dry bag much of the time and I mostly just used my watch to switch to workout mode, bolus as needed, etc. The phone and RileyLink each went in their own separate smaller dry bag, and then I put those plus the pump inside a slightly larger dry bag with the tubing strategically angled at 45 degrees at the edge across the closing. As I folded it over, I would angle the tubing a little more towards vertical so that by the fourth fold, the tubing was coming straight out smack in the middle. This was to avoid the tubing getting pinched when I clipped the ends of the dry bag together.

What it looked like at camp in the rain:

For hiking, I clipped it via a light carabiner to a shoulder strap on my pack and then tucked it inside a strap on my waist belt to keep it from swinging around as I walked. It survived some pretty rough times, including five falls (all while I was sick–more on that further below) and one time forgetting to unclip before swinging my pack down, so I would call this a success.

Looping while hiking a brutal trail

Actually looping well was somewhat harder than figuring out the gear.

When my husband and I hiked this trail 14 years previously, we did it 8 days. It felt too leisurely then, so we said at the time that if we did it again, we’d plan a shorter trip. We planned it this year for 5 days. That was a swing too far in the other direction. It was hard. Although we took short breaks, we had no time to hang out on the rocks this time, watching hawks and other birds play in the air currents. I missed that.

This time, we hiked all day, every day. We had little to no time to hang around camp, play camp games, go swimming, or do anything like that. We hiked 12.5 hours on day 3. (Thank you again to Moira and Rachel, two recent college grads from the US who were doing a very similar loop as we were–regretting their 5-day plan like we were–and with whom we teamed up to make the final push to our sites that day.)

I got sick. I still have no idea if it was a reaction to heat, as it came the day after a very hot day in which I didn’t refill my water when I should have and had some possible heat exhaustion symptoms, or us getting uncharacteristically sloppy with water treatment, but something prompted my body to stage an emergency exit drill for about a day-and-a-half of the 5 days. I do not recommend this experience. (A big thanks to my husband and son, who both carried extra those days to help me, and who made me feel good about toughing it out.)

In my experience, day 1 is always weird. Whatever T1D settings seem to work that day rarely work the rest of the trip. Then I was sick over days 2-3, making blood sugar management extra challenging. So I didn’t really nail my routine until day 4. What ended up working well was:

- adjusting my basal pattern so that my daytime basals were about 60% of usual

- adjusting my daytime insulin sensitivity factor up by about 75%

- adjusting my insulin to carb ratios down by about 50% during the day, underbolusing for all daytime food by giving only about 20-25% of recommended amounts, and making sure to start walking right after eating

- running on workout mode while hiking (my workout mode target is 8.0 mmol/L versus 5.5 mmol/L the rest of the time)

- keeping lifesavers to hand (not in my pack where I needed to take off the pack or have someone pass them to me), having a few lifesavers here and there as needed, and not logging those carbs on Loop

- running everything the same as usual after I was done hiking each day (same basals, ISF, carb ratios, targets)

That last point was the biggest change from non-looping backcountry trips. Typically, I adjust all my basals down, including a minor reduction overnight, but because Loop was able to adjust for post-hiking variation, I didn’t need to.

tl;dr For looping in the backcountry, I recommend a multiple dry bag assembly, bringing backups, and not getting sick. I found it worked well to have a hiking time and non-hiking time protocols. During hiking time, I lowered basals about 60%, raised insulin sensitivity factor about 80%, lowered carb ratios about 50%, raised target BG, underbolused for food by giving only about 20-25% of recommended amounts, and used unannounced partial low treatments to head off lows. After each day’s hiking was done, I used my normal settings. Happy hiking/paddling!

2 thoughts on “Looping in the backcountry”

Thanks for sharing! I’m also looping and camp and hike often. it’s cool to read about your experience and know that other folks are out there doing it too! Sorry to hear you got sick–glad you made it out ok and had a great supportive team.

Great article! I also am a 36 year vet of Type 1 diabetes. I love the outdoors and this summer my older teens and I are going to do a 3 day backcountry hike. I was happy to come across your article as it was very enlightening and makes me less anxious. Thank you.